Introduction

Hypnagogic state, or hypnagogia, has long been a a research topic with major interest. In fact, the first descriptions of hypnagogic phenomena dated back all the way to the 1600s1. However, it was not until the mid-19th century that sleep researchers such as Alfred Maury coined the term1. Even though definitions may vary, in terms of sleep, hypnagogia generally sum up thoughts, images or sensations that occur at sleep onset1,2; there is overall a very strong consensus on the hypnagogic state occurring during NREM1. However, is that all there is to it?

Furthermore, hypnagogic imagery is extremely common in humans3. Most humans have reportedly run into it at some point in their life, actually! And that obviously includes polyphasic sleepers, and even more so in beginners who are new to napping. But is it any good if it is mostly comprised of NREM1?

This post will:

- Entail the differences between hypnagogia, general hallucinatory observations and dreaming

- Showcase the physiological features of the human body and sleep stages during hypnagogia

- Display some usage of hypnagogic naps in sleep research

- Outline certain method(s) to achieve hypnagogia

- Clarify the pros and the cons of hypnagogic naps in polyphasic sleeping

- List certain cautions

Content

- Differences between hypnagogia, hallucinations and dreaming

- Physiology of hypnagogia

- Hypnagogic imagery in polyphasic sleeping

- Methods to achieve hypnagogic naps

- Cautions

Differences between Hypnagogic State, Hallucination & Dreaming

In research, admittedly there has been certain confusion in categorizing hallucination. Specifically, hallucination during wake state includes subjective perceptions (e.g, auditory, visual) that are not real. In the scope of this discussion, however, we focus on the borderline sleep-wake state and distinguish these phenomena.

Clarification

Below are the differences that can at times be confusing4, especially for polyphasic sleepers.

- Hypnagogia include two types: hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations.

- The familiar hypnagogic state features short-lived experiences during the transition from wake to sleep.

- Hypnopompic hallucination is seemingly less common knowledge; in contrast with hypnagogic condition, this consists of transient experiences during the transition from sleep to wake (semi-awake). The continuation of dream sequences that progresses for seconds or minutes even after wakefulness represents mixed REM and waking EEG.

- Hypnagogia are still generally associated with NREM sleep.

- Dreaming, on the other hand, occurs during the classic sleep state. A key trait of dreams is the fact that the dreamer is immersively both a spectator and a direct actor. Most dreams also occur during REM sleep (and much less so during NREM sleep). As a result, dreams can contain entire plots, scenes, many characters; furthermore, dreamers only recall dreams after spending time actually sleeping.

- Overall, hypnagogic state is less vivid than dreaming. However, a normal hypnagogic experience rarely evokes intense emotions.

- Sleepers may quickly forget dreams upon awakening; on the other hand, they often remember hypnagogic experiences well.

- Multisensory experiences (e.g, simultaneous visual and somatic perceptions) are prevalent in dreaming. However, only one of said modalities occur for hypnagogic hallucinations, or different modalities in one sequence. In other words, hypnagogic hallucinations appear more one-dimensional.

- Different brain regions undergo activation under during REM sleep and NREM sleep. For example, prefrontal brain areas are active during REM sleep; yet, cortical areas are more active during NREM sleep.

Physiology of Hypnagogic State

Although “sleep onset” may seem like nothing much for exploration, hypnagogic hallucinations actually have quite a few interesting findings and features. Research so far also experiments with hypnagogia during the daytime shuteye sessions.

- Eyelid stillness for approximately 15 seconds1. This observation marks the first stage of sleep onset.

- Alteration in time perception during sleep2. Specifically, it is common to already spend tens of minutes into a nap before participants feel like they spent 10-30 seconds in the hypnagogic state. This interesting point, therefore, sheds light on the concept of “time jump” during sleep. That is, the actual sleep duration and perception of time are possibly underestimated during light sleep. See Sleep Tracking.

- NREM1 can further break down into 9 substages5. However, sleep researchers only rely on these substages to measure hypnagogic EEGs. Basically, substage 9 is the appearance of a first complete spindle (or start of NREM2). The transition still models NREM1-NREM2 sleep stages, with the dominance, gradual disappearance of alpha waves and the start of theta waves.

- As said earlier, hypnagogia overall express less dreaming agency than REM-dream reports6.

- Individuals with frequent hypnagogia may have enhanced cortical responsivity4.

Dream Contents during Hypnagogic Naps

- Less than 3% of mentation reports after ~15-300 seconds of eyelid stillness included four major dream features1. These features include: Hallucination, self-representation, narrative plot and bizarreness. Thus, hypnagogic reports are more like “micro-dreams”, or the middle ground between hallucinations and REM dreams4.

- Usually, less than half of the reports contain hallucinatory and narrative elements1.

- Hypnagogic dream features also interestingly show an order of appearance. For example, the order is: visual > self-representation > motor ~ plot > bizarreness > audition ~ emotion < somatosensory1. This process is deemed logical because of the gradual construction of dream elements. It is also in line with another quantitative linguistic analysis7.

- At either awakening or sleep onset, the feeling of falling down an abyss was the most frequent hallucination; 15.5% of 3204 participants ran into this hallucinatory content3. Next is the feeling that some entity is present in the room, at 8.9%3. This is also similar in hypnopompic state.

- Overall, there is more action, such as talking to others, others talking, agency of other entities from REM-dream reports. Hypnagogic reports, in contrast, generated shorter words on average and less action6.

- Interestingly, hypnagogic contents about the future disappear as humans fall asleep8. This is especially significant for dream contents collected no less than 75 seconds after shuteye. Moreover, recalling of present and past events remains largely unchanged. For example, “I will do X tomorrow” references before shuteye usually fades after participants wake up.

Hypnagogic Imagery in Polyphasic Sleeping

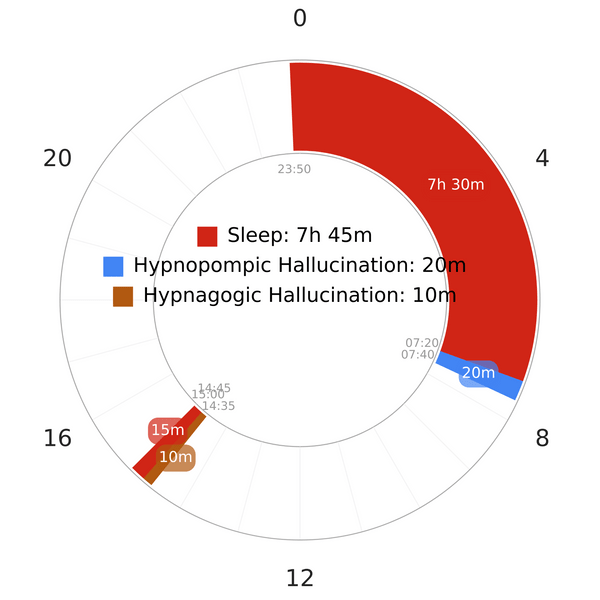

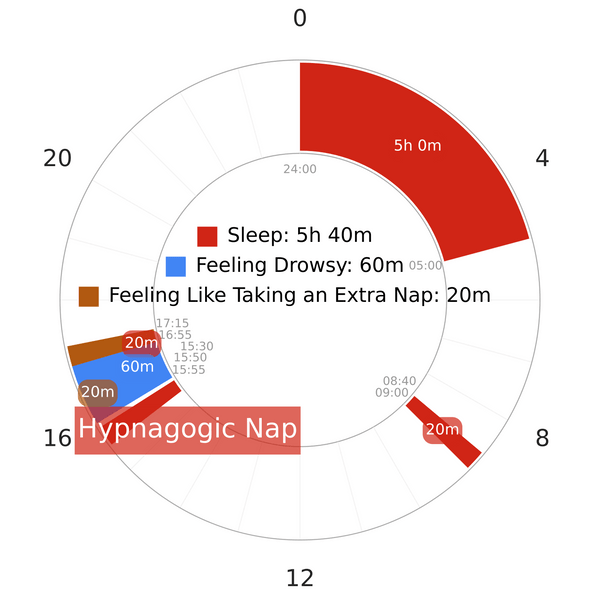

Community Experiences

Over the years, hypnagogic imagery or hallucination is very common in polyphasic sleeping. However, the majority of these incidents occur for beginners learning to fall asleep in naps. Typically, wandering thoughts before falling asleep in naps help contribute to causing hypnagogia. The naps would then often feel “light” and not very rested because objectively, there is not really any actual rest.

Oftentimes, waking up remembering some faint dream contents may suggest a misleading picture of a REM nap. However, not all dreaming instances are created equal. In earlier adaptation stages, REM sleep may not repartition into naps so fast.

Furthermore, there is no record on long-term practice of hypnagogic naps in the community. Rather, such encounters often come and go.

Pros

- Suitable for experimenters. These individuals do not have any confined sleep schedules, so they can train to induce hypnagogia in any naps. Non-reducing sleep schedules (usually polyphasic variants with short daytime naps) are the best bet.

- Great for “-AMAYL“ polyphasic schedules. Similar to the first point, these schedules do not have a fixed amount of naps on a daily basis. Therefore, sleepers can pick a nap or two to “experiment” with hypnagogic imagery sometimes.

- Hypnagogic state is also similar to relaxed wakefulness, or in a way, meditation. Most notably, in history, famous nappers like Albert Einstein tapped into hypnagogic naps to boost creativity9. Therefore, this imaginative napping method may benefit individuals with occupations heavy on the creative side.

- In normal, healthy individuals, hypnagogia are generally harmless, in terms of content3. Thus, this tactic is a cheap way to practice dream recalling.

- Very handy for emergency sleep reduction situations. Even though non-nappers may struggle to fall asleep, their subjective performance and alertness may slightly improve after closing their eyes for some time.

- Since hypnagogic naps take advantage of mostly sleep onset, waking up is extremely easy, or even natural after mere minutes5. As a result, there is often no sleep inertia to hinder their performance right after awakening. This, again, can be very crucial during situations that require sustained reaction and precision.

- Hypnagogic naps are often very short (5-20 minutes), so time investment is very little. It is also practically easy to set up; basically, just a private place with limited sounds to concentrate.

Cons

Although there seems to be many compelling reasons to attempt hypnagogic naps, there is a fair share of cons.

- These light naps usually do not provide any truly restorative sleep stages. Even NREM2 duration is often minimal. As a result, body repairs (SWS), memory consolidation (REM) or motor memory consolidation (NREM2) will most definitely not occur.

- Napping under hypnagogic conditions do not alleviate homeostatic pressure. This process also means that objective alertness may not improve after waking up, or last for long. It is then increasingly difficult to remain alert especially in Stage 3.

- During polyphasic adaptations, just seconds of shutting eyes can lead to a massive oversleep. The intense sleep pressure from reducing polyphasic schedules facilitate sleeping at almost any hours, especially during Stage 3.

- Hypnagogic naps may disrupt an ongoing nap. Sleepers may wake up and find it impossible to return to sleep. Hence, it is necessary to pay attention to the next sleep session to not oversleep. Similarly, a core sleep may suffer from a random hypnagogic state, although it is less common.

- These naps generally do not have the long-lasting and satisfying effects of intense dreaming like a REM nap.

- Hypnagogic naps may also trick polyphasic sleepers into thinking they actually get REM sleep, while an EEG sleep tracker says otherwise. Refer to Covert REM sleep Model for more information.

- Not everyone enjoys hypnagogic hallucinations. These may even be predictors of serious medical conditions. Refer to the Caution section below for more information.

How to Achieve Hypnagogic Naps

For those who are interested in an alternate state of dreaming, hypnagogic naps can do the job very well. The dreaming experiences can be very eerie and intriguing. While it is natural to run into this type of naps, there are well-established methods to learn the trick faster.

- Prior waking experiences can shape dream contents in the next sleep session, even if it is right after the activity. For example, 48 out of 485 participants recalled Tetris-related dream contents when they played Tetris before napping10. This result, again, speaks volumes about how waking experiences can influence dreaming.

- Repeated training of daydreaming before napping, and keeping the nap duration short.

- Sensory deprivation. For instance, the usage of a “ganzfeld” can effectively create hypnagogic hallucinations before napping2. A classic example is gazing at a homogeneous and unstructured visual field. Alternatively, staying in a sound-free environment can achieve the same effect.

- Try to sleep on a uniform, flat surface. Slight elevation of upper body during napping (as part of a manual protocol) reduces hypnagogic imagery generation after napping11. It is inferred that disturbances in sleep environment can and will negatively affect the experience.

NOTE:

- Regardless, the ability to recall experiences may vary among individuals. It may also not work at all for some.

- In addition, refrain from long exposure to sensory deprivation as it can generate intense hallucinations and even anxiety when awake.

- Hypnagogic naps are bound to be less common as a polyphasic adaptation progresses because of homeostatic pressure and faster SOREM.

Cautions with Hypnagogic Experiences

To expand the previous point in the Cons section, there are certain cautions of hypnagogia to beware of.

- In cataplectic narcolepsy, muscle weakness and highly vivid hypnagogia are often simultaneously present4.

- Schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease also yield hallucinations4. Thus, it is common for schizophrenics to experience interrupted sleep.

- Rampant drug and alcohol use and narcolepsy can cause frightening hypnagogia together3.

- The high frequency of hypnopompic hallucinations is also prominent in younger individuals, current drug users, bipolar and other psychotic disorders3.

- The sleep onset/awakening hypnagogia often do not point to any associated pathology in most cases3. However, there is the risk of self-harm and pain infliction on others if an individual is terrified by their own experience. Regardless, this is only notable in narcoleptic individuals.

- Hypnopompic hallucinations, such as the incubus phenomenon, are associated with nocturnal hallucinations and sleep paralysis4. Its prevalence is also massively familiar, with a 30% chance during lifetime.

- Specifically, occasionally waking up feeling horrified, paralyzed, or heavy on the chest has occurred from time to time in humans.

- The experience with sleep paralysis can amplify schizophrenics’ delusions.

- If you experience more daytime hallucinations or any other suspicious medical conditions, consult a doctor.

Conclusion

In sum, the popular hypnagogic state at sleep onset and after waking up is mostly innocuous. Most importantly, it even seems “natural” as part of a napping experience for polyphasic sleepers. While bearing some resemblance to REM dreams, hypnagogia confine to NREM1. Thus, while it can serve some useful individual purposes and diversify a polyphasic sleep experience, generally the consistent practice of such napping habits is uncommon.

The nature of such naps also aligns more with the casual “shuteye” naps that monophasic sleepers occasionally take. In many cases with short durations (less than ~5-10 minutes), they may not behave as a “true” nap where sleepers actually fall asleep. Special cautions also have to be given to individuals with psychosis, mental conditions and other sleep disorders, however.

Main author: GeneralNguyen

Page last updated: 20 April 2021

Reference

- Rowley, Jason T., Robert Stickgold, and J. Allan Hobson. “Eyelid movements and mental activity at sleep onset.” Consciousness and cognition 7.1 (1998): 67-84. [PubMed]

- Wackermann, Jiřı́, et al. “Brain electrical activity and subjective experience during altered states of consciousness: ganzfeld and hypnagogic states.” International Journal of Psychophysiology 46.2 (2002): 123-146. [PubMed]

- Ohayon, Maurice M. “Prevalence of hallucinations and their pathological associations in the general population.” Psychiatry research 97.2-3 (2000): 153-164. [PubMed]

- Waters, Flavie, et al. “What is the link between hallucinations, dreams, and hypnagogic–hypnopompic experiences?.” Schizophrenia bulletin 42.5 (2016): 1098-1109. [PubMed]

- Kaida, K., Nittono, H., Hayashi, M., & Hori, T. (2003). Effects of Self-Awakening on Sleep Structure of a Daytime Short Nap and on Subsequent Arousal Levels. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 97(3_suppl), 1073–1084. doi:10.2466/pms.2003.97.3f.1073. [PubMed]

- Speth, Jana, Clemens Frenzel, and Ursula Voss. “A differentiating empirical linguistic analysis of dreamer activity in reports of EEG-controlled REM-dreams and hypnagogic hallucinations.” Consciousness and cognition 22.3 (2013): 1013-1021. [PubMed]

- Speth, Clemens, and Jana Speth. “The borderlands of waking: Quantifying the transition from reflective thought to hallucination in sleep onset.” Consciousness and cognition 41 (2016): 57-63. [PubMed]

- Speth, Jana, Astrid M. Schloerscheidt, and Clemens Speth. “As we fall asleep we forget about the future: A quantitative linguistic analysis of mentation reports from hypnagogia.” Consciousness and cognition 45 (2016): 235-244.

- J Graham Beaumont. Brain Power : Unlock the Power of Your Mind. London, Grange Books, 1994.

- Kussé, Caroline, et al. “Experience‐dependent induction of hypnagogic images during daytime naps: A combined behavioral and EEG study.” Journal of Sleep Research 21.1 (2012): 10-20. [PubMed]

- Nozoe, Kenta, et al. “Does upper-body elevation affect sleepiness and memories of hypnagogic images after short daytime naps?.” Consciousness and cognition 80 (2020): 102916.

I have a rather simple experience (I assume it’s common?) I play soft background sounds to help with my sleep. A thunderstorm with a soothing brass instrument mix. Anyway, I’ve noticed that I can mentally turn-off this music just before falling asleep and not hear the music again when I wake up until I intentionally listen for it. Okay, I’m guessing that’s normal?

But, this morning I noticed that I could mentally turn-off the brass part but still listen to the thunderstorm and thought this is pretty weird. I could turn on the trombone and I could turn it off mentally and I could turn off all sounds if I tried. I am absolutely sure I was awake.

I’ve googled and searched and the best shot at understanding this is right here I suppose.

Any explanation? Is this common? I’m 66 yrs old and this is new to me. I’m just curious.