Introduction

Non-rapid-eye-movement 1, or NREM1, is the first stage of the NREM sleep category. It is the first stage of light sleep and researchers often refer to it as “sleep onset”. Alternatively, it is also sometimes called “relaxed wakefulness”1. From the name, it is also the first sleep stage in a sleep session. The other NREM sleep stages are NREM2 and Slow-wave sleep.

In the context of polyphasic sleeping, NREM1 is largely an “outlier” sleep stage due to its usual insignificance. However, research on this sleep stage over the years does show specific traits that polyphasic sleepers more than often will question some of their own nap(s). Although there are still possibly hidden mechanics regarding this sleep stage, this post will display its characteristics and relevance in polyphasic sleeping.

Characteristics of NREM1

Despite its overall brief presence during sleep, NREM1 still has certain features that distinguish it from other states of sleep and wakefulness.

EEG features

- NREM1 is nearly indistinguishable from wakefulness, functionally. What this means is that NREM1 has very negligible, if any visible functions for human health.

- In addition, it occurs at sleep onset and is at the junction of wakefulness and sleep. People who wake from this stage remark that they barely get any sleep. They are often still well-aware of the surrounding even with closed eyes.

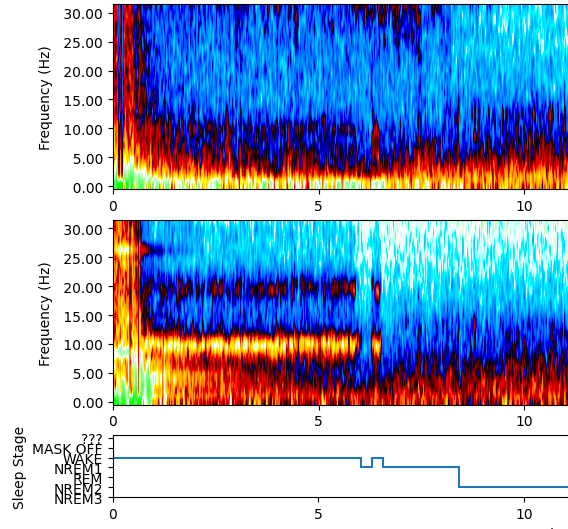

- During this sleep stage, the most common EEG activity starts slowing down; prominent alpha activity occurs at the posterior sites and theta activity at the anterior sites2.

- Notwithstanding, there is some noticeable EEG difference between NREM1 and wakefulness2.

- The first block is the usual front position while the second is occipital (back position).

- The wakeful state has low amplitude and high-frequency activity.

- On the contrary, the frequency begins to slow down at NREM1 with more alpha activity as stated.

Other notes

- Up to date, there has been no discovery on any vital purposes of NREM13.

- Assuming normal sleep conditions and no interrupted sleep, NREM1 always has the least percentage and duration among all sleep stages.

- A typical NREM1 shuteye oftentimes does not enhance objective cognitive functions of sleepers upon awakening. This is because they have not gotten any actual rest. As a result, they are bound to make mistakes or repeat the same mistakes they made before the sleep session.

- It is possible to lucid dream during NREM1. Specifically, this phenomenon is often referred to as “Wake-Induced Lucid Dreaming” (WILD). This is a state where sleepers enter sleep while retaining their prior wakeful states. Dreams from NREM1 and REM sleep have been notably similar4.

- Hypnagogic imagery4 and hypnic jerks5 in general have a direct relationship with NREM1 specifically. For the latter, muscles may twitch when sleep first initiates. Most hypnic jerks are normal in healthy humans. However, some individuals may suffer from a sleep-related movement disorder6 with intensified and frequent hypnic jerks. This can be highly disruptive to overall sleep quality.

- Zen meditation and other regular forms of meditation activities also consist of mostly NREM17. This is because meditation is often a form of relaxation method.

How much NREM1 per day is healthy?

Along with no research on vital functions of NREM1, there is also no documented study on the optimal amount of NREM1 to obtain daily. Under normal nocturnal sleep of healthy adults, only mere percentages of NREM1 are observable. In a meta-analysis, normal adults (both sexes) have an average of ~9.7% of NREM1 per total sleep of ~7 hours in bed8. Thus, it is important to know that personal sleep onset value should neither be too high nor too low.

In polyphasic sleeping, mostly on reducing schedules, NREM1 is often very short, or even negligible on more restrictive sleep totals. Furthermore, NREM1 duration is short even in short naps of adapted sleepers. Most notably, it is impossible to completely eliminate NREM1 no matter how extreme a polyphasic schedule. This is because a certain period of time is always necessary to transition from wakefulness to sleep.

Excessive NREM1

The following (of many more) characteristics can explain why a poor sleeper spends more time in NREM1 than sound sleepers:

- Trouble getting actual sleep (insomnia)

- Trouble staying asleep (interrupted sleep)

- Poor sleep hygiene. This includes not sparing enough time to cool down for sleep.

- Certain medical conditions, such as ADHD9, may also worsen overall sleep quality and delay sleep by boosting NREM1 duration.

Possible Consequences & Correlates of NREM1

Even though it is unknown what biological processes NREM1 serves, there are red flags with poor amounts of vital sleep stages (REM and SWS) and high amounts of light sleep.

- Increased mortality rate: All-cause mortality has a positive correlation with the increased amount of light sleep, including NREM110. The study suggests that shallower sleep with reduced vital sleep will increase mortality rate. Therefore, it appears that NREM1 may be even negative in excess.

- Sleep quality vs sleep duration: One study indicates that sleep quality, or sleep depth, is a strong biomarker for greater tissue density in the brain11. Because NREM1 resembles a wakeful state, spending most time in bed asleep and getting enough vital sleep stages would be a better choice than inflating sleep duration with NREM1.

Conclusion

As of current knowledge, NREM1 is not a vital sleep stage. Up to date, there is no research that shows what roles it can play in humans, unlike SWS and REM sleep. While adequate sleep hygiene and a healthy lifestyle may improve sleep onset issues with NREM1, polyphasic sleep can also assist with faster sleep onset.

Main author: GeneralNguyen

Image by: Dakyne

Page last updated: 19 January 2021

Reference

- Green, Simon (2011). Biological Rhythms, Sleep and Hypnosis. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-230-25265-3.

- Brown, Ritchie E., et al. “Control of sleep and wakefulness.” Physiological reviews (2012). [PubMed]

- Carskadon MA, Dement WC. Normal human sleep: an overview. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. 2011;4:16-26. http://apsychoserver.psych.arizona.edu/JJBAReprints/PSYC501A/Readings/Carskadon%20Dement%202011.pdf.

- Stumbrys, Tadas, and Daniel Erlacher. “Lucid dreaming during NREM sleep: Two case reports.” International Journal of Dream Research 5.2 (2012): 151-155.

- Syring, Kaitlyn (2008-02-28). “A case of the jerks”. The University Daily Kansan. Archived from the original on 2010-07-26. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- Cuellar, Norma G., Debra Whisenant, and Marietta P. Stanton. “Hypnic Jerks: A Scoping Literature Review.” Sleep medicine clinics 10.3 (2015): 393-401. [PubMed]

- Doufesh, H., Faisal, T., Lim, K.-S., & Ibrahim, F. (2011). EEG Spectral Analysis on Muslim Prayers. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 37(1), 11–18. doi:10.1007/s10484-011-9170-1. [PubMed]

- Boulos, M. I., Jairam, T., Kendzerska, T., Im, J., Mekhael, A., & Murray, B. J. (2019). Normal polysomnography parameters in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(19)30057-8

- Sobanski, E., Schredl, M., Kettler, N., & Alm, B. (2008). Sleep in Adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Before and During Treatment with Methylphenidate: A Controlled Polysomnographic Study. Sleep, 31(3), 375–381. doi:10.1093/sleep/31.3.375. [PubMed]

- Zhang, Jingjing, et al. “Influence of rapid eye movement sleep on all-cause mortality: a community-based cohort study.” Aging (Albany NY) 11.5 (2019): 1580. [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, H., Taki, Y., Nouchi, R., Yokoyama, R., Kotozaki, Y., Nakagawa, S., … Kawashima, R. (2018). Shorter sleep duration and better sleep quality are associated with greater tissue density in the brain. Scientific Reports, 8(1). doi:10.1038/s41598-018-24226-0. [PubMed]