Introduction

Wake-induced lucid dreaming, or wake-initiated lucid dreaming (WILD), is an alternate way to achieve lucidity while sleeping; specifically, it is the practice of falling asleep with consciousness1. At its core, it showcases the ability to enter the lucid dreaming state while retaining the conscious state during wake. Because of this unique feature, it may often be very challenging to differentiate between dream states.

Up to this point, the understanding of WILD with research-based evidence remains limited. In other words, lucid dreaming as a category remains understudied. In the polyphasic sleep community, there has been some interest in achieving wake-induced lucid dreaming. However, to many polyphasic sleepers, the overall mechanics remain largely unclear. Furthermore, since there has not been any long-term attempt at WILD, many polyphasic sleepers are not aware of this special dreaming technique.

Because of the intricate nature of WILD, this post will:

- Distinguish between the standard lucid dreams and wake-induced lucid dreams

- Demonstrate EEG readings on WILD activity

- Outline steps to do WILD

- Apply WILD technique to polyphasic sleep

Content

- Differences between WILD and DILD

- Examples of WILDs and Eye-movement correlates

- Ambiguities in classifying lucid dreams

- A step-by-step approach to achieve WILD

- WILD and polyphasic sleep: Is it worth it?

Differences between Wake-induced Lucid Dreaming and Dream-induced Lucid Dreaming

Dream-induced Lucid Dreaming

The regular type of lucid dreaming that people often refer to has a scientific name as well. Dream-induced lucid dreaming (DILD) is the original and popular form of lucidity. Apparently, sleepers would fall asleep, enter REM sleep, and start dreaming. However, at some point during that dream, they become “aware” that they are dreaming – this is a classic DILD1,2.

For more detailed descriptions on DILD, refer to this lucid dreaming article.

How WILD is Different from DILD

Additionally, there has also been certain misconception on how WILD works. The wake-initiated state seems to convey that WILD happens during NREM1, a sleep stage that can also create somewhat vivid dreams. Nevertheless, research evidence says otherwise, and for good reasons.

- Wake-induced lucid dreams are a result of prior physiological signs of awakening3. Furthermore, this awakening is the real wakeup process from sleep.

- Random, transient awakening periods during REM sleep are common, although most regular lucid dreamers do not have any subjective impression of being awake3.

- The brief “awakening” during REM sleep is often very short in a wake-induced lucid dream. It can last for only 1-2 seconds3. Furthermore, sleepers may not be aware that they have somewhat woken up. WILD dreamers can also continue into the subsequent uninterrupted REM period.

- Both types of lucid dreaming tend to occur in the later half of the night, where REM sleep becomes the dominant sleep stage. However, in the case of WILD, morning and afternoon sleep sessions statistically can induce more WILD instances2,3. Still, morning sleep would favor WILD more than afternoon rest sessions. This observation also fits the circadian process of REM sleep regulation.

- There have been much fewer WILD reports than DILD reports, thanks to WILD’s complex mechanics.

- For a dream to qualify as a WILD4:

- There are less than 2 minutes of REM that disrupt the last period of wakefulness and the eye-movement signal that shows the onset of lucidity.

- Sleepers have to enter the lucid dream directly with full awareness of doing so.

Overall, WILD still has associations with REM sleep, but to a lesser degree than a DILD.

Some Examples of Wake-induced Lucid Dreaming and Eye-movement Correlates

Because WILD’s behavior sparks characteristics of REM sleep, below are some examples of how a WILD looks. Note that these are collected from the dreamers in the Polyphasic Discord.

Monophasic Sleep

“As I closed my eyes, after some time, I saw an image of a mountain. With my experience, I know full well that this is a hypnagogic image. Then, I saw myself walking toward the top of the mountain. However, it was not clear how fast I walked, because I felt very light. The next thing I knew, I was certain that I heard the roar from the abyss below the mountain. And finally, probably within mere seconds, I was falling down the mountain, into a seemingly endless pit. My body became weightless, and gradually synchronized with a vacuum space.”

– An anonymous monophasic sleeper.

Polyphasic Sleep

Everyman 1

“I woke up from the nap halfway through and recalled a fight with my family. However, the wake period was very short. I lied down and closed my eyes again to resume sleep in just a matter of seconds. This time, once again, I started the same dream again, that fight. Yet, I first saw only the two family photos of us together. Then, I “thought” that I tried to reach them, but they kept getting further away, and disappeared. Now it was just me, alone in the room. But wait, was I awake? I think so, but not “real wake”. I looked around before the door suddenly slammed shut behind my back.”

– J, a Biphasic sleeper (ongoing adaptation) with a WILD nap.

Everyman 3-extended

“I felt like I was more awake in this nap than I was”.

– PoisonNectar, who experienced WILD in the second nap on E3-extended (during adaptation)

Analysis of Dream Contents

- All examples qualified for a WILD experience. This is because there was a strong indication of “wakefulness” during a dream.

- Hypnagogic imagery was present during two examples, paving the way for a WILD. Thus, the next section (Steps to WILD) will detail how important hypnagogia’s role is.

- There is potentially bias in the dream contents because of the lack of an electrooculography. Measuring eye movements is key to detecting changes in REM sleep continuity.

- It is reasonable to expect a “choppy” nap and a WILD experience together. This is because the very short wake periods interluding the REM block suggest that the sleeper is able to return to REM sleep immediately.

- Between the brief wakefulness and the first minutes of the next REM onset, a WILD likely occurs. Thus, the E3-extended sleeper’s remark that she “felt more awake” checked out.

- In the Polyphasic Discord community, we often refer to this napping phenomenon as “Napaware“.

- Despite that the Zeo did show her “wake” during REM sleep, these were only “microarousals”. Hence, the wakes were more like her impressions of being awake1; this also matches with Psychophysiologist Stephen LaBerge‘s description of a WILD.

- The sensation of being “awake” during REM sleep (but not the actual awakening from sleep) stresses on the unique behavior of REM sleep. There is a reason REM sleep is considered “paradoxical sleep”. Recall that brainwaves during REM sleep resemble those during wakefulness. As a result, this example would have been difficult to identify as a “WILD” had there been no EEG reading besides the simplistic sleep report.

Electrooculography Detection of Wake-induced Lucid Dreams

To quote the paper directly, the above physiological channels are3:

- T3 and T4 are left and right temporal EEG.

- LOC and ROC are left and right eye movements using an electrooculography (EOG).

- The electromyography (EMG) measures chin muscle tone.

- The electrocardiography (ECG) tracks heart rate.

Both eyes’ movements in the above channel directly correlate with the subject’s WILD exposure.

- Specifically, the subject woke up at signal 1 (See number on EMG line).

- Then, he returned to REM sleep after 40 seconds at signal 2 (EMG line).

- After that, he realized he was dreaming 15 seconds later, at signal 3 (Bottom ECG line).

- Next, he sang between signals 3 and 4. Note that, though, it was his task in his own lucid dream.

- Finally, he started counting between signals 4 and 5.

All in all, this experimental WILD protocol enabled comparisons between the left and right hemisphere during two tasks. There is a pattern of heartrate acceleration-deceleration at at awakening (signal 1) and lucidity onset (signal 3). Refer to the quoted research paper above for comparisons with DILD measurements.

Certain Ambiguities in Classifying Types of Lucid Dreams

With the existence of multiple dream phenomena, it suddenly becomes baffling to know which is which. To date, the community has collected experiences with the following:

- Sleep paralysis

- Nightmares

- False awakening dreams

- Lucid dreams (DILD and WILD)

- Out-of-body experience (OBE) (very rare)

- Hypnagogic state

- Sleep terrors

The list may go on. At times, it may not be possible to correctly classify which dream is which. This is especially problematic for polyphasic sleepers who are adapting to their schedules. The repartitioning of REM sleep and other sleep stages as well as sleep deprivation symptoms likely blur their perceptions of a dream. Thus, we commonly hear intensified dreaming experiences that contain elements of a DILD and non-lucid dreams. For example, spotting a lucid dream inside of a normal, vivid dream can either be a false awakening dream or… DILD.

Let’s take a look at an example in the community.

Wake-induced Lucid Dream, False Awakening or Dream-induced Lucid Dream?

Below are the details of a polyphasic sleeper’s schedule, dream log and analysis.

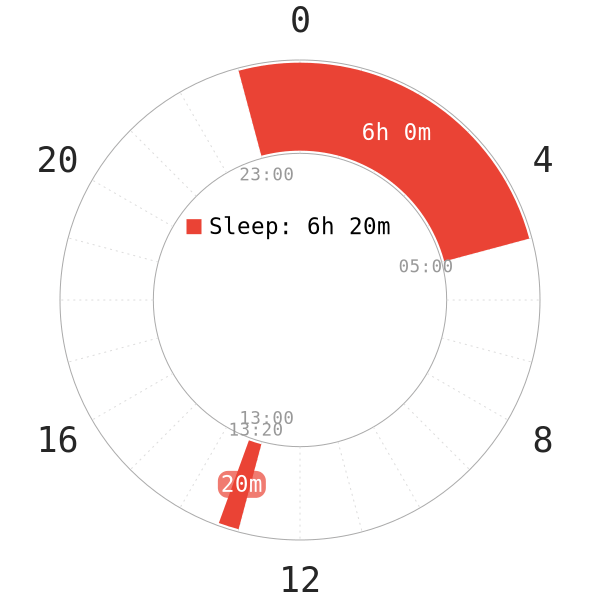

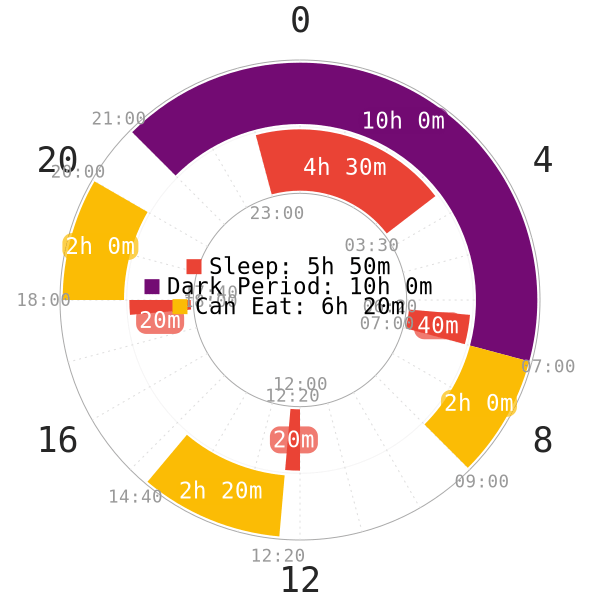

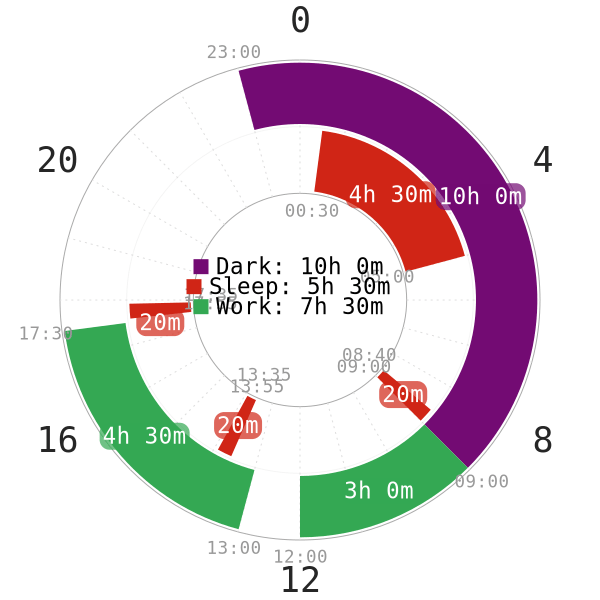

E3-extended Scheduling

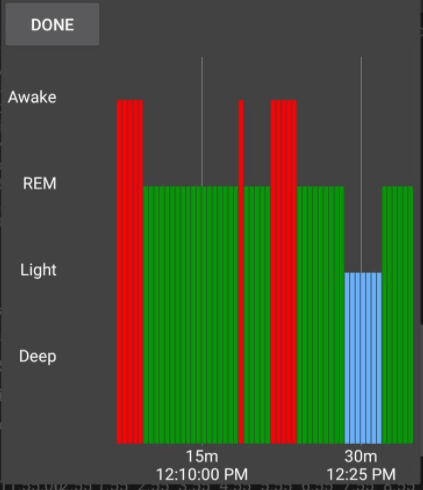

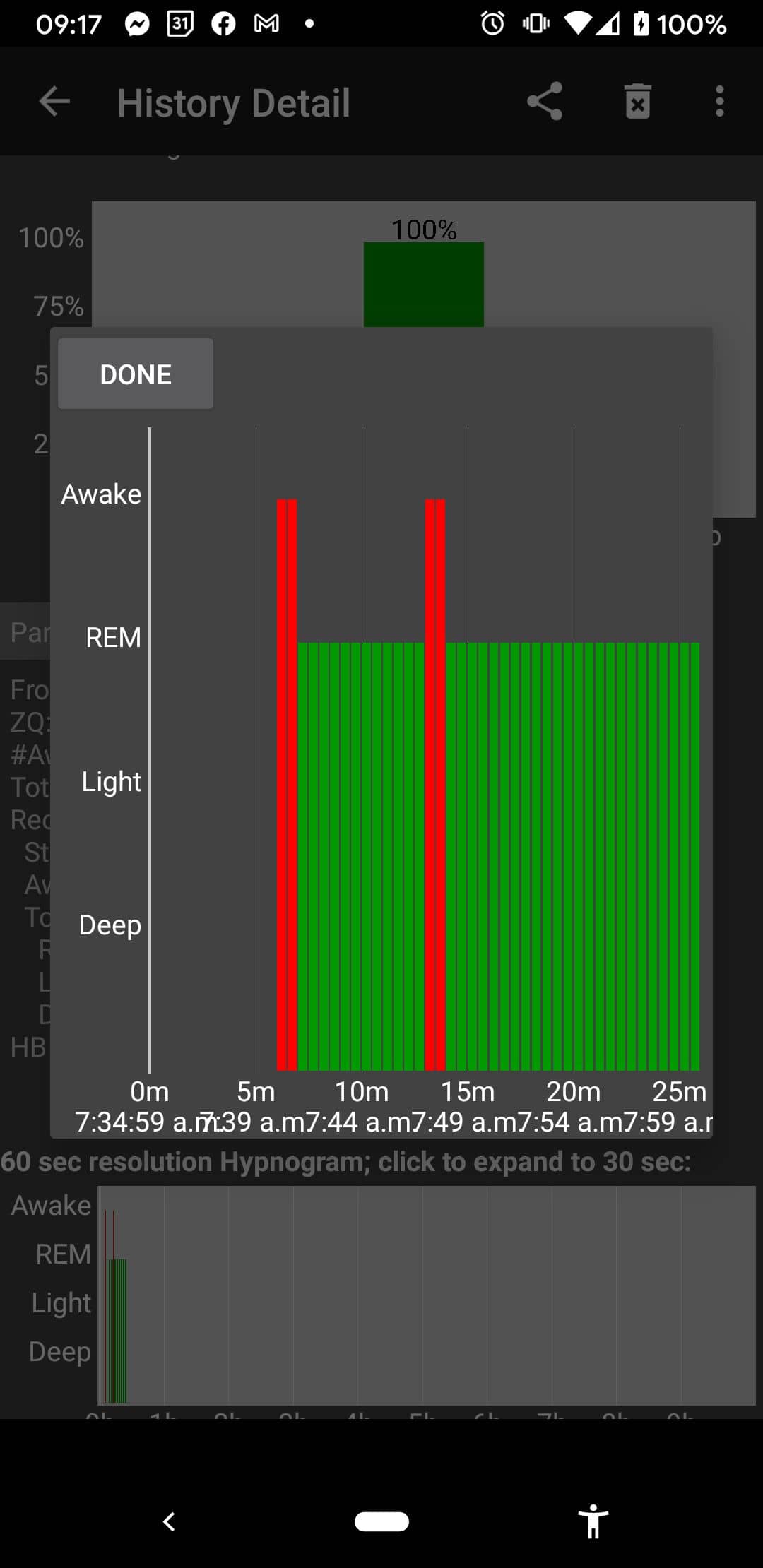

EEG Recording of the First Nap (7:40-08:00)

Dream Content

“Took a while to fall asleep. Still feeling upset from fight day prior. Had a nightmare that my oversleep preventer went off but went haywire. It was loud and there was nothing I could do to stop it. Additionally, it switched to French partway through (???). My girlfriend was woken and yelling at me about it. I willed myself actually awake as I realized the French bit was impossible. By then I was in the last 5 minutes of the nap.”

Other notes:

“I also have two sets of sounds playing. Rain in the first 10 minutes and ocean sounds in the last 5. There is complete silence in between. I think I woke to ocean sounds but I don’t remember.”

– Russet, a dream report from her first nap on an ongoing E3-extended adaptation.

Dream Analysis

There are a couple important points to remember here.

- The second “wake” (red tint) on the Zeo reading shows that Russet woke up in the middle of her nap. However, she did not recall doing so.

- There was a difference in timing of her perception. Specifically, she “knew” well that she was in the last 5 minutes of the nap. As said in the first point, the wake period did NOT match this description.

- Even though Russet did physically wake up to to check her phone, she was able to re-enter REM sleep immediately for the last 5 minutes of her nap. However, there was no extra dream content recalling after this awakening. Still, it was clear that she did not simply “estimate” that there were 5 minutes remaining in the nap. Her act of waking up confirmed it. However, the Zeo did not record this awakening at all.

- Since she woke up in the dream, it implies a false awakening dream. Thus, it appears to be a regular DILD, just a bit more intense with the false awakening.

- Based on the setup of sounds (to aid with falling asleep), the Zeo indicated that her second awakening (10 minutes into the nap) matched with when the rain sounds turned off.

So, did Russet achieve a WILD?

Theories

After discussing with the dreamer herself and some other experienced lucid dreamers, here are our theories:

- Russet did actually achieve a WILD, but the Zeo did not properly show it. This is understandable because microarousals can be difficult to detect and the Zeo’s average accuracy is only ~80%.

- She had a false awakening. When she checked the clock, it actually showed a false time. This is because clocks are messy in dreams; if you just glance at them, they may fool you. They certainly do it to me (one lucid dreamer said) and the Zeo took that as a “wake” state of mind. It is similar to the bug they have with NREM1 or something.

- She did not actually log correctly the time perception during the nap. Although it seems that she strongly believed in what she saw, distinguishing the wake and REM state can be misleading.

- Because of her false awakening, it suggests that she did fall asleep before lucid dreaming. This effectively contradicts a WILD, where sleeper’s consciousness has to remain intact like during the wake state.

Verdict

Russet did NOT achieve WILD. This is because she started out with a non-lucid dream (nightmare). Then, she slowly drifted into a false awakening dream where she started being aware of her wakefulness. Therefore, this is “a lucid dream inside a non-lucid dream”.

Overall, there are likely many similar cases that resemble Russet. As a result, identifying a WILD can be more frustrating than ever.

A Step-by-step Approach to Achieve a Wake-induced Lucid Dream

For polyphasic sleepers or nappers interested in practicing WILD, see the guide below1.

Step 1: Understanding the Optimal Timings for WILD

As said earlier, it is possible to kickstart WILD via a couple ways.

- At sleep onset, NREM1, preferably a daytime nap5.

- Waking up from REM sleep then returning to REM sleep right away5.

- Morning (REM-peak hours) and afternoon hours favor WILD more than nighttime hours.

Step 2: Taking Advantage of Hypnagogic Imagery

Hypnagogic imagery is presumably a powerful component to induce WILDs5,6.

- First, relax in bed. Close your eyes and relax your head, back, body and legs.

- Next, focus your inner attention to the images that first appear. They may look simple, but they will develop into a complex series or sequences later.

- Do not start engaging it yet. At the same time, do not appear too detached. Let the dream contents build up, and “float” or “sink” through them. At this stage, observe their formation until you can comfortably dive into it, consciously.

- Try to see if you start feeling a string pulling you forward or backward. Similarly, a sensation of “being sunk” also does the job.

- Lastly, stay conscious for some more time and you will be truly experiencing a WILD!

In a way, after you have mastered hypnagogia, you can take it a step further to become a WILD-er. If you wake up from a core sleep, say ~5 hours, and return to bed some time later (interrupted monophasic sleep), you can advance the hypnagogic imagery method the same way.

Step 3: Focusing on Body and Breathing

- In this step, you should breath normally and slowly. Kind of like regular intervals. Additionally, inhaling with a distended belly is a good idea. The opposite goes for exhaling. This technique is called “Pot-shaped” breathing.

- In case you lose consciousness, try to bring back the body sensations that you created. For example, feeling hollow from the inside or scanning your body.

- Find a comfortable sleeping position! For this guide, the supine position seems the most ideal.

Step 4: Counting Sleep

- To be able to pull this step off, you first have to let go of all worries and concerns. For first-time practice, it is going to be tough, but it is part of learning a new skill.

- Focus on whether you are actually dreaming right now by asking the question, “Am I dreaming?” repeatedly.

- Next, start counting from 1, and with the above question. You also may have to start over if you reach ~100 and see no results. However, keep being persistent! At some point you will be aware that you are dreaming.

- Note that this step is often the hardest because it is very easy to drift into sleep completely. Polyphasic sleep, which repartitions vital sleep into core(s) and nap(s), greatly facilitates sleep with increased sleep pressure!

Do not forget the most old-schooled tricks in the book! Reality checking and dream journaling even if your naps do not go well are keys to understanding your dreams better!

Wake-induced Lucid Dreaming and Polyphasic Sleep: Is It Worth It?

According to a single-case study, using Galantamine to help induce WILDs seems to partially help the sleeper7. However, the number of WILDs is still noticeable lower than DILDs. Also, it is necessary to fully understand Galantamine’s mechanism of actions before following in the same footstep.

Notice that WILD attempters actively try to “segment” their monophasic core sleep into 2 sections. Does this sound familiar? So, does that mean Segmented sleep is the ultimate goal for achieving WILDs? What about other polyphasic schedules?

While the answer lies in the mechanism of REM sleep, REM peak and how “fragmented” sleep initiates lucid dreaming, the final answer is far from simple. There are some noteworthy points to consider WILDs on your polyphasic schedules. Still, any polyphasic schedules with a core sleep or nap around REM peak hours are great candidates for WILD practice.

List of Considerations

- WILDs are much more difficult to induce than DILDs. It may not be worth your efforts in the end.

- Experiencing WILDs is a strong option to interrupt your core sleep and your nap(s). This is especially common in first-time nappers or dreamers. You may have just ruined your own sleep quality by actually waking up and not being able to sleep again.

- Unless your polyphasic schedule has a decently high amount of total sleep (at least ~6-7h), attempting WILDs in a core sleep is strongly discouraged.

- Practicing WILD on a non-reducing schedule before your polyphasic attempt is a good idea to gauge.

- It is possible to experience WILD unintentionally2! Thus, you may not have to invest as much and can still run into it from time to time. Any sleep sessions around REM peak are “natural habitats” for WILDs.

- Coming across sleep paralysis during a WILD is not uncommon. Waking up abruptly from REM sleep can, in fact, expose you to sleep paralysis, incubus or demonic encounters1.

- Given some training and familiarity with WILD state, it is still possible to wake-induced lucid dream without interrupting sleep much. The aforementioned two EEG readings showcase that REM sleep can be stable and continuous after brief awakenings. Polyphasic sleep also has different mechanics of regulating homeostatic processes to keep sleep pressure sufficiently “high” in a REM-peak sleep session, for example.

- Polyphasic sleep’s SOREM mechanics in naps enable a faster “recovery” of REM duration when you return to REM sleep again.

- Individuals with very low dream recall frequency may not succeed at recalling any dreams still.

- Focusing on counting or breathing too much may also disrupt the process of falling asleep.

The Verdict

As there is not enough data on WILD, it is not fully possible to completely rule out WILD as a would-be practice. Indeed, WILD is very unique and does not look like any ordinary dreaming experiences. Sometimes, the best course of action is to… do nothing and let things play out. As such, regularly logging dreams after awakening is an intelligent method to differentiate between dreams.

Conclusion

In conclusion, wake-induced lucid dreaming is a familiar yet highly challenging to pull off. Its nature is also potentially ambiguous and misleading with other vivid dream contents. In a way, WILD is a deeper state of hypnagogia. Regardless, there are ways to approach WILD and enjoy the experience on a polyphasic sleep schedule. With that being said, there are notable cautions for WILD lovers on a polyphasic schedule. It is necessary to consider both pros and cons of WILDs before practicing it willy-nilly on a polyphasic sleep adaptation.

Main author: GeneralNguyen

Page last updated: 22 April 2021

Reference

- LaBerge, Stephen, and Howard Rheingold. Exploring the world of lucid dreaming. New York: Ballantine Books, 1991.

- DeGracia, D. J., and S. LaBerge. “Varieties of lucid dreaming experience.” Individual differences in conscious experience. Amsterdam: John Benjamins (2000): 269-307.

- LaBerge, Stephen. “Lucid dreaming: Psychophysiological studies of consciousness during REM sleep.” (1990).

- Levitan, Lynne, et al. “Out-of-body experiences, dreams, and REM sleep.” Sleep and Hypnosis 1.3 (1999): 186-196.

- Stumbrys, T., Erlacher, D., Schädlich, M., & Schredl, M. (2012). Induction of lucid dreams: A systematic review of evidence. Consciousness and Cognition, 21(3), 1456–1475. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2012.07.003. [PubMed]

- Stumbrys, Tadas, and Daniel Erlacher. “Lucid dreaming during NREM sleep: Two case reports.” International Journal of Dream Research 5.2 (2012): 151-155.

- Gish, Elliott Everett. “LUCID DREAMING: A WAKE-INITIATED-LUCID-DREAM (WILD) APPROACH.”

Hi, I wasn’t clear from your otherwise excellent post whether or not you are saying that WILD “can” or “cannot’ occur during REM sleep.

I researched WILD as part of a 6 month project (for my masters in psychology) teaching a group of 12 people how to have lucid dreams. 6 succeeded in WILD more or less regularly.

My own experience – which I think is consistent with the research – is that while it is in fact easier for WILD to occur in the early morning, next easiest in the afternoon, I have experienced WILD near the beginning of the sleep cycle.

In fact, on meditation retreats, I’ve found after 30 minutes or more of meditating, it’s possible to have WILD be successful regardless of the time of day or night or the relationship to the sleep cycle.

I’d love to hear if you have some references to research on this. Thanks so much.

Greetings,

Thank you for reading the post and taking the time to post a question as well as my late reply.

From the cited research papers, WILDs are associated with REM sleep. This has been directly stated in the article I wrote, in the beginning paragraphs. However the difference here is that it is less than a 2-minute REM period that has elapsed. So it does appear in REM sleep but not a long, continuous chunk of REM sleep like what is shown in any regular EEG reading.

Furthermore, your experience with WILDs at the beginning of the sleep cycle may be attributed to some partial REM sleep deprivation (which is very common for monophasic people). There is another article that addresses this in the Dreaming hub, and you can check out the explanation. But basically, REM sleep deprivation (monophasic sleep) can result in the early appearance of REM sleep in the first cycles at night as a way to compensate from the prior deprivation.