Introduction

For those who love either regular or vivid dreaming, or even lucid dreaming, being able to recall dreams makes their dreaming life so colorful and imaginative. While some individuals can recall at least one dream each night, some can only recall a couple dreams each month or a couple weeks. While there are differences in dream recall frequency attribute to differences in brain activity during sleep, there appears to be a lot of uncertain scientific and psychological factors behind dream forgetting.

This blog focuses on:

- The potential factors that cause the forgetting of dreams after awakening.

- Discussing if polyphasic sleeping is the ultimate tool to improve dream recall.

42 adapted polyphasic sleepers (to at least one schedule) have been interviewed for a survey questionnaire on the following questions:

- Do adapted polyphasic schedule(s) enable them to recall more dreams than during adaptation?

- Compared to monophasic sleep, does adapted polyphasic experience improve their dream recall or that they still forget as many dreams?

Alongside these questions, dream reports from some of these sleepers will demonstrate how and if polyphasic sleep may contribute to the changes in the dream recall pattern. Would dream recall benefit from polyphasic sleeping?

Content

- Basics of Dreaming

- Basics of Dream Recalling

- Factors of Dream Recalling/Forgetting

- Survey Results

Polyphasic Sleep & Why We Forget Dreams

Basics of dreaming

Dreaming has always been common during sleep. Whether an individual recalls dreams multiple times a week or only a couple times a month, dreaming experience in humans varies. Aside from dream recall frequencies, dreaming experiences portray a lot of interesting ideas to explore. One of the most common misconceptions in dreaming is in a polyphasic sleeper’s experience below.

“So dreaming for me was always something I struggled with [redacted]. Obviously, I got interested and started to collect info on dreaming. And the first step I needed to take was to increase the dream recall rate, which felt like impossible at first. So, I started to dream journal, meditate, use mantra, etc. However, these didn’t really help me. Or maybe I should say it just wasn’t enough.

After that, I gave up on dreaming for quite a while. I think it’s not doable for me; but then I discovered polyphasic sleep and decided to try it out [redacted]. And it gave me some hope.”

– Zecq, a DC1 sleeper with an ongoing adaptation, reported from the Discord.

From the above excerpt, one of the most common misconceptions that new polyphasic sleepers often have is that they do not dream during sleep. This seems to justify why they do not recall any dreams. In fact, humans do always dream, but a lot of cases do not recall their dreams upon awakening. Dream patterns are observable during sleep, typically from eye movements during REM sleep1.

It is also worth noting that from EEG studies, dreaming occurs even in NREM sleep2 (NREM1, NREM2 and SWS). Thus, this makes it possible for dreams to come from all sleep stages3. What polyphasic sleeper Zecq mentioned has to do with his dream recall ability, not that he did not dream. Another misconception that has been flying around for a while is that dreams only occur during REM sleep. However, several sleep studies have refuted this2,3,5.

Basics of dream recalling

- Dream recall refers to the process of recalling or remembering dreams.

- Forgetting dreams in this context refers to the inability to recall dreams after awakening and how humans forget dreams as time goes on.

- For the most part, from hundreds of polyphasic sleep dream logs, the majority of successful dream recallers fall into the second category. Their dreams usually did not last for longer than a couple minutes after awakening.

However, there are factors to retain dreams longer.

- Reporting dreams right upon awakening

- Being naturally good dream recallers

- Having very vivid dreams that left a strong impression afterwards

- Experiencing dream contents that recurred on a regular basis.

Because of the transient nature of dreams, they are generally hard to remember and easy to forget1,4. Conclusively that REM sleep has a higher dream recall rate than SWS sleep and light sleep stages2,3.

Factors that contribute to the forgetting/recalling of dreams

The fragility of dream remembering is attributable to several factors. These range from sleep stages at the moment of awakening, substance use and natural dream recall frequency to Sigmund Freud’s dream recall theories (e.g, repression). All these factors serve to demonstrate how easy it is to forget dreams.

This section will detail the most common or known factors that contribute to dream forgetting.

Sleep Stages & Brain Activity During Sleep

There is an EEG study on university students with a normal monophasic sleep schedule and no daytime napping habits.

- A higher frontal theta activity and alpha activity (5-7 Hz) was a solid predictor for a successful dream recall after awakening from REM sleep.

- Additionally, a lower alpha activity (8-12 Hz) of the right temporal area is also a contributor. This process involves the thalamo-cortical network that results in a lower cortical activation upon awakening from NREM sleep2.

- An increase in alpha power would lead to poorer memory encoding performance, an important process that contributes to dream recalling.

There is also a polyphasic-related study. Participants followed a sleep protocol of sleeping a 75m core sleep alternated by each 150m staying awake. This study also delivered some interesting results for dream recall in relation with sleep stages and awakening time.

The experiment lasted for only 40 hours, which was not enough for participants to completely adapt to this polyphasic pattern. There was a recovery sleep episode after this “multiple-nap” experiment.

Data Interpretations

- As a sleeper enters SWS, which generates oscillation behavior of NREM sleep, their synaptic responses impair. They become non-responsive to the surrounding.

- Eventually, this act dramatically reduces dream recall thanks to delta waves and an increase in sleep spindle activity5.

- However, dreaming in NREM2 resembles REM sleep to some extent. This is typical during 15 minutes prior to awakening, lower EMG and the density of eye movements.

- This second study also confirmed the necessary characteristics of a successful dream recall from the first study, regarding alpha activity during NREM sleep.

Implications for polyphasic sleeping

Polyphasic sleepers with no EEG equipment to record their sleep should not be quick to conclude the following:

- They wake up from REM sleep.

- Their nap(s) contain predominantly REM sleep if they successfully recall dream(s).

- However, temporal units can determine if a sleep block is mostly NREM or also contains REM sleep.

- Similarly, even with no dream recall from any said sleep blocks, these sleep blocks may contain some amount of REM sleep.

- Being in REM sleep does not guarantee a successful dream recall incident.

- It is also reasonable to forget dreams upon awakening from a heavy sleep block that is predominantly SWS.

Substance Use

Certain substances suppress REM sleep, thus possibly nullifying dream recall in some individuals. Frequent cannabis users6 and the use of SSRIs report this7. However, the cited study on cannabis indicated that there may be differences between laboratory setting and home setting. Certain results of dream recall frequency are irreplicable in different studies.

This study demonstrated that there was no difference in dream recall of frequent cannabis users, even if these users experienced bizarre dreaming experiences6. Other substances that decrease the amount of REM sleep include MAOIs, selective norepinephrine uptake inhibitors and non-specific monoamine reuptake inhibitors8.

However, the difference in settings, genetics, etc. in different individuals require more research for these results to be consistent.

“Honestly, my dream recall at the time was terrible. I think it had much to do with my THC and nicotine use at the time. But my recall got better when I became clean.”

– Ratheka, an adapted E2 sleeper, on her dream recall experience with substance use.

Repression

Sigmund Freud initiated the model for repression, a hypothetical model for dreaming.

- It indicates that the forgetting of dreams in humans is largely a product of resistance and censorship9.

- More specifically, the theory reflects the propensity for humans to deny and avoid negative, threatening or painful experiences to forget their dreams; as such, Freud believed that dreams are representations of fulfilments of repressed wishes and desires.

- Freud also stated that the process of forgetting dreams was a result of mental resistance to the dream. Dreams often exhibit their peak power upon awakening, leading to no traces of recalling the dream(s)9.

- Since the contents of the dreams are alien to the ego of the dreamers, they are supposed to forget the dreams in face of reality. Their desires remain unfulfilled.

- In addition, in the case that dreamers only recall some partial or blurry details of a dream, these suggest signs of resistance to the dream itself10.

However, currently the psychoanalytic functions of dream interpretations have developed; they may vary from Freud’s original and controversial theories, so the repression theory may not be clearly applicable in all cases.

Free association

Notably, one psychoanalytic study supported the theory of repression using free association. This is a technique to help patients resolve their inner conflicts by gauging their thoughts and feelings in a relaxed mental state.

25 participants with dream notes were asked to freely associate with 5 elements from their dreams and 5 elements from other participants’ dreams.

- There was a a great activation in skin conductance response.

- More unpleasant feelings were present against unrecognized dream elements (repressed contents)11.

However, in another study of home-recall dream theory experiment, repression did not account for significant reliability12. Thus, repression may only be partially applicable to dream forgetting experiences in polyphasic sleep.

Interference

The interference theory stems from Cohen (1974). It states that dream forgetting is a byproduct of a distraction process via pre-sleep anxiety. In return, it can distract sleepers from recalling their dreams upon awakening12.

- This study also showed the correlation between reduced dream recall and increased dream unpleasantness by interference12.

- Another study showed similar results. Field-dependent male subjects reported less frequent dream recall under the effect of stress. However, they still recalled the most impactful dreams with interference. However, interference did not seem to affect field-independent male subjects13.

The process of dream recalling was likely most ideal condition if it occurs right upon awakening. Delaying the process of recalling dreams result in a less likelihood of recalling them12. This notion also does seem to apply to the majority of polyphasic sleepers who are vivid dreamers, especially those who have formed the habit of logging dreams upon awakening.

Over the years, few of them did admit to forgetting a lot of dreams if they did not report them immediately. Only a couple of them claimed that being anxious before a sleep block would prevent them from recalling dreams. However, the data sample is not expansive enough to draw a concrete conclusion.

Setting

The difference in the settings in certain dream report study has been a plausible possibility to cause changes in dream recall patterns. Most dream studies have been laboratory-based6, while there are only few studies using home settings. There are some postulated reasons in a study with one male subject who spent 45 nights in a laboratory. He was awakened at the end of REM sleep every night14:

- Laboratory dreams are often more banal than home dreams.

- Repression was partially responsible for some unremembered dreams; however, it was not clear how much.

- Unremembered dreams were likely a result of short, prosaic dream details. They occurred some time before the sleeper woke up. Long, intense and impactful dreams were usually recalled shortly upon awakening.

- Dream recall potentially faded very quickly when the gap between the end of a REM period and the awakening time increased. This observation is in line with how certain polyphasic sleepers have trouble recalling dreams if they wake up in NREM2.

Acetylcholine & Norepinephrine in wakefulness & REM sleep

This is a rather new correlation among two neurotransmitters and their role in the neocortical circuits and REM sleep. All this dictates certain aspects of dream recalling.

- Acetylcholine (ACh) release and norepinephrine (NE) release pattern during wakefulness and different sleep stages are important factors15.

- Specifically, NE and ACh release wanes and remains low as sleep begins (entering NREM sleep).

- However, while ACh release increases during REM sleep, NE release remains low during REM sleep.

- Thus, low/moderate ACh release maintains global cortical arousal during REM sleep and wakefulness.

- On the other hand, absence of NE activity during REM sleep is a possible explanation why long-term synaptic changes are difficult to sustain (e.g, memory retention). This in return facilitates dream forgetting upon awakening.

However, more mechanisms of these two neurotransmitters’ roles in memory sustenance and functions in the sleep-wake cycle need further studies, especially when combined with polyphasic sleeping.

Short Sleeper

Short sleepers (those who require less sleep than average to be fully functional) have similar amounts of SWS to normal individuals; however, they have less NREM1, NREM2 and REM sleep duration16. Their monophasic baseline is usually quite shorter than that of average individuals (6h or less to feel fully rested each day).

They are normal, healthy and do not usually require any health or psychological interventions. It is reasonable to predict that shortened REM duration means more difficulty to recall dreams. Although not absolutely conclusive, dreaming experiences from certain short sleepers in the community do reflect their lower dream recall or unchanged dream recall compared to their monophasic schedule.

Some on the other hand have positive feedback on adapted polyphasic experiences. This includes enhanced dream recall, so this varies between sleepers (e.g, low and high dream recallers).

Does Polyphasic Sleeping Help Recall More Dreams or Slow the Forgetting Rate?

Similar to dream forgetting in the previous section, eventually we all forget dreams. This does not matter if we successfully recall them after waking up. However, adapted polyphasic sleepers who pay enough attention to their dreaming experiences generally reported increased dream recall compared to monophasic sleep.

This section will list some dreaming experiences as comparison between during and after the adaptation phase is complete.

Results

- Of the 42 surveyed adapted polyphasic sleepers from the community, 28 reported increased dream recall after the adaptation phase.

- 10 reported either decreased or unchanged dream recall rate after adaptation;

- The remaining 4 were uncertain.

- 30 reported increased dream recall while on an adapted polyphasic pattern compared to their monophasic pattern.

- There were 7 cases with unchanged and decreased dream recall while being adapted;

- The remaining 5 did not remember their dreaming experiences due to past adaptations long time ago. Alternatively, they did not run into strong or bizarre dream contents to remember them.

- Dream contents were also diverse, ranging from reflections of real life to surreal types (fictions).

- All adapted schedules resemble standard variants on the website unless specified otherwise.

Some Dreaming Experiences

Everyman 3

“During the adaptation to E3, I stably recalled one dream a day (after nap 1). Most often, they were quite bright and long. Closer to the fifth week of the adaptation (stage 4), my dream recall was getting poorer and poorer. Among the dreams that I occasionally managed to recall ,there were almost no bright ones.

I was disappointed; but two days before the end of the adaptation, I first got a lucid dream, bright and long (using the reality check technique). After that there were no vivid dreams at all.

There were only a few similar to NREM1/2 dreams (more like hallucinations). For example, a dream where I’m sitting between palms. I also almost never recall any dreams on monophasic sleep”.

– Sekvanto, an E3 sleeper.

NOTE: Sekvanto is also a short sleeper with 6h monophasic baseline to be fully functional each day. She also has strong sleep propensity during mid-late afternoon hours (~5-6 PM).

“I’d say dream recall is pretty much the same for both during and after adaptation. However, I get slightly more dreams after adaptation in comparison. And I get most dreams in the first nap, but dream recall is best for the second one. Still, generally I do dream in most of my naps. Also to be fair, I have vivid surreal dreams more so than I do normal ones.

I’d say I recall more dreams on E3 than on my 48h mono. Yet, my regular monophasic sleep probably gives more dream recall than E3.”

– UncertainBeing, an E3 sleeper.

NOTE: Similar to Sekvanto, this is also a short sleeper, but with a high dream recall rate after adaptation.

Everyman 3-extended

“I have always had good dream recall, but I think polyphasic sleep slightly improved it. I would say nap 2 (noon) is the strongest, but I recall a lot of dream from the core as well.”

– Allyz0r, a 3-year (and counting) E3-extended sleeper.

“After adapting and even during Stage 4, I didn’t dream at all, or at least I couldn’t recall any. Maybe one small core dream, but that’s it. I do believe that my core covers the basic sleep needs, with the naps acting as NREM2 wakefulness sustainers. I’ll check that hypothesis next month, when I can afford an EEG.

As for recall, I remembered pretty much everything about the dream at ~06:20. I also remembered directly after wake (and realizing Isa Briones was not in my house) at 05:30. So 50+ minutes recall, though I tried to remember it by thinking about it until I got the chance to log.

On monophasic sleep, my dreams were pretty mundane; I usually didn’t remember them for more than a few moments. They just became jumbled with memories of reality. My dreams were not exactly outlandish, but mostly situations could easily happen in reality. Just me talking to people I saw every day at locations I was daily. Of course, there are exceptions, but I only recall one.”

– Hackerman, an E3-extended sleeper.

NOTE: Hackerman is one typical case for seemingly subpar dream recall rate. Nevertheless, he is capable of recalling intensely vivid dreams on a polyphasic sleep regime.

Biphasic-X

“I feel as if my dream recall after adapting is better than it was during adaptation. At the start of my adaptation it was shitty like it was on monophasic sleep. However, after a few days, it started to get better. It kept improving gradually until around day 30. Since then it hasn’t really changed.

Sorry that this part isn’t in a lot of detail, I don’t really remember when everything happened. It’s definitely the core that gives me the most recall. I never have any dreams in my nap if it’s short. If it’s a longer nap, sometimes I recall a dream, but it’s not very vivid; I can only remember foggy details.

I’d say that when I was on monophasic sleep, my dream recall is around 4/10. I recalled some details from dreams about once every three nights, but most of the time they weren’t at all vivid. Never had any lucid dreams either. Nowadays, I’d rate my dream recall about 8/10. I remember a lot more from my dreams every night and they’re a lot more vivid.

So, I’d say my dream recall has improved a lot. Also, I’ve had maybe 6 lucid dreams, which is pretty cool and a big improvement from monophasic sleep”.

– Weaver, a 2-month non-reduced biphasic sleeper.

NOTE: Even non-reducing biphasic sleeping can make a difference in sleep architecture and change dream recall rate, although this is possibly highly individualistic.

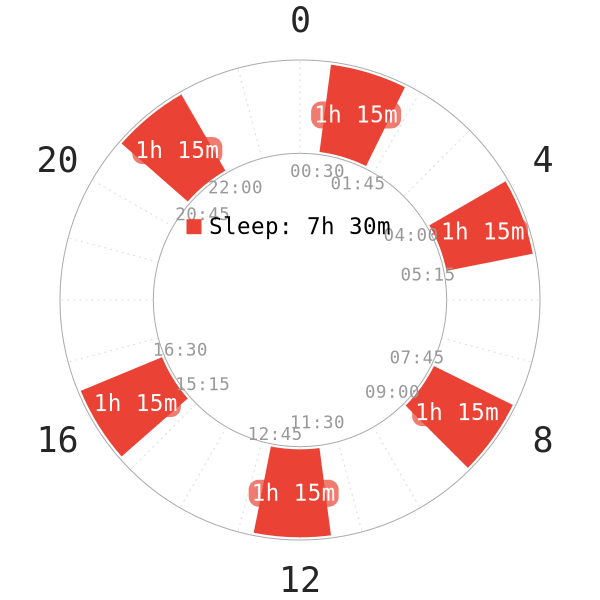

Dual Core 1/ Everyman 2

“My dream recall on E2 is overall not that great. After both 20 minute naps, I forget about 50% in the first few minutes. The most I can recall is from the 4h30m core.

I would rate my DC1 experience to be better than E2 in terms of dream recall. For me monophasic sleep has better dream recall than DC1, but I forget my dreams pretty quickly overall.”

– Erthiros, a DC1 & E2 sleeper.

NOTE: Different sleep patterns can yield different dream recall experiences. In this case, DC1 is more favorable for dream recalling, mostly because of the longer REM sleep block in the morning hours. This sleep session usually contains a higher percentage of REM sleep than a mere 20-minute nap of E2.

Everyman 2-extended

“Overall recall was lower during adaptation, partly because I had to learn how to REM nap in the first place. Also, because by the time inward adaptation, I have practiced it a bit to have a somewhat higher recall rate. Note that the overall recall rate was still sh*t and I forgot about 2/3 of my naps.

In the end it was okay, but without practice, I forgot everything except maybe one single picture. I don’t feel like I’m getting that, at least I don’t notice it. I mean during REM peak they are likely more lewd; Otherwise, I can’t see another pattern in my dreams. But even the lewd ones are of completely random context.

My dream recall on monophasic sleep was about a solid minus five. I didn’t dream at all for at least several years before polyphasic sleep. 99,99% of the time I didn’t dream; and if I did, I forgot the content within an instant. So polyphasic sleep is a major improvement.”

– Feili, an E2-extended sleeper.

NOTE: Feili is a prime example of very poor dream recall ability that can drastically improve upon switching to a polyphasic regime.

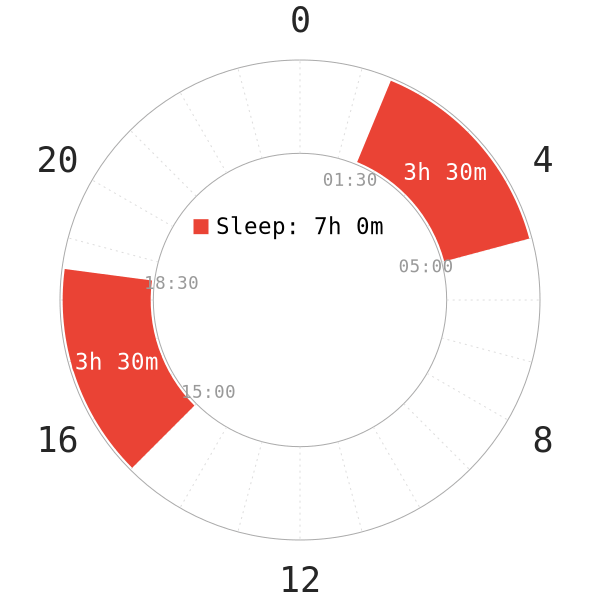

Segmented

“I literally never recall any dreams, sometimes one in a few months. Being adapted to segmented didn’t change anything in terms of that. I would say my dream recall is low even after adapting to Segmented.”

– ModoX, a Segmented sleeper.

NOTE: This case shows no difference in dream recalling in a monophasic sleep and a segmented sleep pattern. Results were equally poor, but this is possibly due to missing out on REM peak. Refer to the napchart below.

Tri Core 1

“I remember pretty much all of my dreams and I retained a high level of consciousness every time. All cores and naps. Naps felt really long, but actually they were just 20 minutes. I remember dreaming and doing lucid a lot.”

– Tomorrow, a TC1 sleeper.

Everyman 1

“During adaptation, I definitely recalled less dreams. Nap gives me the most dream recall. After adaptation, I recalled even more dreams. More from the nap and less so from the core. I think E1 gives a better dream recall rate because it doubles the dream recall opportunity. 2 sleep blocks compare to 1 from monophasic.”

– Soulless, a 1-year (and counting) E1 sleeper.

NOTE: From the data in the community, only 50% of the adapted E1 sleepers experience naps with only light sleep. In the case of Soulless, it is more likely that he did manage to get some REM sleep in the nap. In addition, he is potentially an excellent dream recaller.

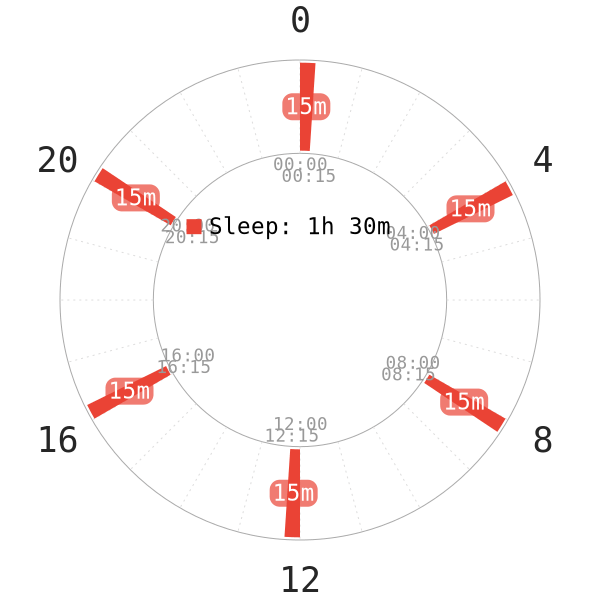

SEVAMAYL

“Adapted E3-extended strict vs adapted SEVAMAYL? Definitely more in SEVAMAYL because it’s a lot freer with the natural wakes. I can get up from a nap after 12-15m if I want to. I know I can just nap again when I get tired enough.

Alarms are the main thing that distract me from mulling on my dreams as I awaken. Just by sheer number of wakes. Monophasic sleep without alarms is the best easy dream recall. This is because I’m waking from vivid heavy REM closest to REM peak without any pressure to get up and do something else.”

– Aethermind, a long-term polyphasic sleeper with successful adaptations in both E3-extended and SEVAMAYL.

NOTE: This is a good example of how certain post-awakening procedures can facilitate dream forgetting. Similar to certain repression and interference methods, it is easy to forget dreams quickly if the individual in question is occupied with other things at the time.

Triphasic

“After being adapted, I wake up every other time (core) with dream recall. However, I forget them quickly. The dreams did not stay in my mind for long after awakening. My dreams definitely lasted longer on monophasic than this and they were also much more common.”

– Timothy, a Triphasic sleeper.

Honorary mention:

Uberman

“However, by the end of 20-25 days, I eventually succeeded in adapting to the schedule and achieved my goals. I equipped myself with an alarm clock that I regularly reset every 4 hours. My excitement Iasted for about 5-6 months, at which time I started to have a few doubts.I also experienced a Strange Sensation that I only understood Iater: I missed dreams. I am a dreamer. Sleeping without dreams was totally unknown to me. Lack of dreams– not lack of sleep restricted me, restricted my imagination.

It was evident to me that I needed the subconscious input and production represented by dreams. As this nourishment was missing, my imagination and my artistic activity started to suffer. I felt like I was using the power of a battery without ever recharging it (not a physical battery, but a sort of creative one). I was suffering a kind of imaginative damage, due primarily to lack of dreams. My oneiric self was totally eliminated.

I therefore decided to interrupt my experiment.”

– An insomniac/non-mutant eclectic artist who adapted to Uberman in the 1950s (~30 years of age)17.

NOTE

Despite being adapted to such an extreme version of Uberman, the artist reflected on the disappearance of dream recall. Theoretically, it is possible that the Uberman schedule does not retain the usual amount of REM sleep. This would reduce dream recall. The artist himself was not a sleep mutant and was able to sleep through 8 hours monophasically after this Uberman experiment17.

As soon as he returned to monophasic sleep, his dream recall ability recovered. In addition, whether Leonardo Da Vinci actually followed the Uberman sleep pattern is unknown. This Uberman dreaming experience seems to be in line with what a 2-year adapted Uberman short sleeper Yin Yang reported from the Discord. She did not experience vivid/lucid/intense dreaming; this is contrary to what extreme polyphasic sleep schedules originally promise.

However, despite these negative dreaming experiences, Steve Pavlina (~6.5h monophasic baseline post-Uberman) reported more lucid and overall vivid dreaming instances during his adapted Uberman experience18.

Further analysis and inferences

The size of the data pool may not be sufficient to draw stronger conclusions regarding polyphasic sleeping and enhanced dream recalling in each particular case. However, polyphasic sleepers who were able to recall dreams frequently are overall satisfied with their dream recall ability, whether they develop it after exposure to polyphasic sleeping or not.

- The forgetting of dreams which occurs sooner or later upon awakening did not seem to bother these sleepers; with increased dream recalling and multiple sleep blocks each day that polyphasic sleep offers, this means more chance to recall dreams from each sleep block.

- Most notably, sleep blocks around sunrise hours seem to provide vivid dream recall for the majority of cases; this also fits the natural circadian of REM sleep distribution.

- Thus, polyphasic sleepers often run into either new or repeated dream contents on a regular basis; dreams in the next sleep blocks would replace forgotten dreams. Ultimately, this forms a cycle of stably frequent dream recalling.

More mechanisms of REM sleep distribution as well as neural activations during each polyphasic sleep pattern need more future research. However, based on the survey, polyphasic sleeping is worth an attempt for the pursuit of lucid dreaming or vivid dreaming experience.

It is also wise to acknowledge that polyphasic sleep in general and extreme polyphasic schedules in particular do not automatically guarantee increased dream recalling or slow down the dream forgetting rate over monophasic sleep.

Conclusion

In sum, forgetting dreams is very common. There are a lot of factors that contribute to the forgetting of dreams and inhibiting dream recall. The diverse dreaming content in polyphasic sleeping seems to at least secure dream recall ability regardless of how quickly dream forgetting begins. Multiple sleep blocks each day increase the chance to recall dream(s) from each block.

In addition, polyphasic sleep likely changes waking habits and awakening times, which affects dream recall. However, it remains unclear how each polyphasic pattern may affect dream recall capability or underlying processes that contribute to suppressing dreams. There are also some possible individualistic factors that dictate how certain polyphasic sleepers do not report enhanced dream recall even after completing adaptation. These are intriguing idea for future exploration.

If you are interested in enhancing recalling dreams, you may also like our post “Autogenic Training: A Potentially Visionary Relaxation Method for Polyphasic Lifestyle“.

Main author: GeneralNguyen

Page last updated: 2 April 2021

Reference

- Johnson, D. M. “Forgetting Dreams.” Philosophy, vol. 54, no. 209, 1979, pp. 407–414, www.jstor.org/stable/3750615. Accessed 5 May 2020.

- Marzano, C., Ferrara, M., Mauro, F., Moroni, F., Gorgoni, M., Tempesta, D., … De Gennaro, L. (2011). Recalling and Forgetting Dreams: Theta and Alpha Oscillations during Sleep Predict Subsequent Dream Recall. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(18):6674–6683. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0412-11.2011 [PubMed]

- Cavallero, C., Cicogna, P., Natale, V., Occhionero, M., & Zito, A. Slow Wave Sleep Dreaming. Sleep. 1992;15(6):562–566. doi:10.1093/sleep/15.6.562. [PubMed]

- Sayan, Erdinç. “DREAM FORGETFULNESS.” Metazihin: Yapay Zeka ve Zihin Felsefesi Dergisi, 2, Pp.93-102, www.academia.edu/10168857/DREAM_FORGETFULNESS. Accessed 3 May 2020.

- Chellappa, S. L., Frey, S., Knoblauch, V., & Cajochen, C. Cortical activation patterns herald successful dream recall after NREM and REM sleep. Biological Psychology. 2011;87(2):251–256. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.03.004. [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, Ceri, et al. “P039 REM Sleep and Dream Reports in Frequent Cannabis versus Non-Cannabis Users.” BMJ Open Respiratory Research, vol. 6, no. Suppl 1, 1 Nov. 2019, bmjopenrespres.bmj.com/content/6/Suppl_1/A23.1.abstract, 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-bssconf.39. Accessed 5 May 2020.

- Pace-Schott, E. F., Gersh, T., Silvestri, R., Stickgold, R., Salzman, C., & Hobson, J. A. SSRI Treatment suppresses dream recall frequency but increases subjective dream intensity in normal subjects. Journal of Sleep Research. 2001;10(2):129–142. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00249.x. [PubMed]

- Agargun, M. Y., & Ozbek, H. (2006). Drug Effects on Dreaming. Sleep and Sleep Disorders, 256–261. doi:10.1007/0-387-27682-3_29.

- WHITMAN, R. M. Remembering and Forgetting Dreams in Psychoanalysis. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association. 1963;11(4):752–774. doi:10.1177/000306516301100404. [PubMed]

- Lewin, Bertram D. “The Forgetting of Dreams.” (1953).

- Köhler, Thomas, and Michael Prinzleve. “Is forgetting of dreams due to repression? Experimental investigations using free associations.” Swiss journal of psychology. 2007;66(1):33-40. [PubMed]

- Segall, S. R. (1980). A test of two theories of dream forgetting. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36(3), 739–742. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(198007)36:3<739::aid-jclp2270360323>3.0.co;2-8

- Goodenough, Donald. “Repression, Interference, and Field Dependence as Factors in Dream Forgetting.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1974; 83(1):32–44. [PubMed]

- Meier, C. A., Ruef, H., Ziegler, A., & Hall, C. S. Forgetting of Dreams in the Laboratory. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1968;26(2):551–557. doi:10.2466/pms.1968.26.2.551. [PubMed]

- Becchetti, Andrea, and Alida Amadeo. “Why We Forget Our Dreams: Acetylcholine and Norepinephrine in Wakefulness and REM Sleep.” The Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2016;39(1):E202. doi:10.1017/S0140525X15001739.[PubMed]

- “Short Sleepers- Sleep EBook.” Sleepdisorders.Sleepfoundation.Org, sleepdisorders.sleepfoundation.org/chapter-8-variants/short-sleepers/. Accessed 5 May 2020.

- Stampi, Claudio. Why We Nap : Evolution, Chronobiology, and Functions of Polyphasic and Ultrashort Sleep. Birkhauser, 2014.

- “Polyphasic Sleep Log – Days 25-30 (Final Update).” Steve Pavlina, 20 Nov. 2005, www.stevepavlina.com/blog/2005/11/polyphasic-sleep-log-days-25-30-final-update/. Accessed 5 May 2020.