Introduction

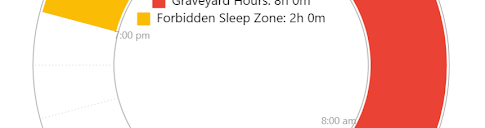

The forbidden zone of sleep (FZS) is a period of time of natural wakefulness right before the onset of nocturnal sleep. During this period, the body has a high tendency to resist sleep and it is usually impossible to fall asleep. Under normal sleep conditions (based on normal nocturnal monophasic sleep and no sleep deprivation), FZS hours vary from 19:00 to 21:00 or 22:001.

It is worth noting that the regular FZS hours are not set in stone; it has the potential to vary between individuals depending on lifestyle. Knowing that this zone exists and how to schedule sleeps around this zone is a perk for polyphasic sleeping. Questions include, but are not limited to:

- Does polyphasic sleeping apply the same principles of FZS as monophasic sleep?

- Are the FZS hours different on polyphasic schedules?

- if it is possible to shift this zone, how can they be different?

- Why do some certain polyphasic schedules not seem to follow the regular hours of FZS?

There are more questions than answers, so this blog will attempt to decipher how the FZS works under different sleep conditions. This depends if sleep deprivation is involved or not. It is also important to address whether standard polyphasic schedules in this community guideline follow the rules of FZS. There will also be a breakdown of FZS hours under normal nocturnal sleep (normal lifestyles) and irregular hours (e.g, shift work).

The role of thyrotropin hormone & sleep deprivation

An evolutionary perspective

Hypothetically, thyrotropin (thyroid-stimulating hormone) surges during the hours of FZS. It acts as a survival enhancer for human beings from an evolutionary perspective2. From the circadian rhythm standpoint, thyrotropin level is low during noon or early afternoon where sleeping is fitting. However, the hormone level raises during FZS, effectively preventing sleep2.

In terms of survival mechanisms, one proposal is that humans are vulnerable to different threats when the night falls (stemming from ancient time). Thus, a period of preparation for safety before night sleep is a high priority. These hours coincide with the FZS and over time humans have become accustomed to staying awake during these evening hours2.

Thyrotropin is a circadian pacemaker that gives signals to the body of sleep hours. The pattern of thyrotropin levels is specifically as follows:

- Sharply increase in the evening.

- Peak around the time of sleep onset.

- Decrease during sleep.

Thyrotropin hormone during sleep deprivation

During sleep deprivation periods in polyphasic sleep adaptations, partial sleep deprivation causes thyroid levels to increase.

- As sleep deprivation persists, at one point thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels decline because of negative feedback by thyroid on TSH release3.

- More sleep deprivation also results in more stress. This theoretically forces the sympathetic nervous system to release more TSH.

- Once the sleeper rests, the thyroid hormone level declines.

Implications for polyphasic sleeping

- During sleep deprivation scenarios (e.g, most polyphasic sleep adaptations), thyroid hormone is said to sharply increase2,3. This is a survival mechanism against sleep deprivation.

- In hypersomniac individuals, thyroid level is low, causing constant sleepiness during the day; on the other hand, insomniacs or sleep deprived individuals have elevated levels of thyroid in the system.

One concerning hypothesis is that it is unknown if continuous failed polyphasic adaptations can lead to the chaotic regulation of thyroid hormone. Alternatively, it may instinctively lower thyroid release in the future when an adaptation starts again, making both falling asleep and oversleeping much easier than before.

Similar to the Oversleeping Syndrome addressed in the community, in the midst of sleep deprivation, sleepers can sleep through all alarms and even stronger external stimuli that they normally would be able to respond to.

Sleep in the forbidden zone

One would ponder if it is completely impossible to sleep in the FZS. People have slept with irregular patterns before, including hours much earlier than the regular night sleep hours, which coincide with the forbidden zone. The answer to this question is, “no”.

- Under sleep deprivation conditions, homeostatic pressure can take over FZS, facilitating sleep at these hours4.

- It is also worth noting that even though 21:00 is borderline with FZS, it is possible and reasonable to start sleeping at this evening hour. This is acceptable if it fits your lifestyle because natural melatonin release starts at 21:006.

- However, under conditions with no sleep deprivation, FZS naps become very light and easy to wake from. They give negligible sleep inertia but also less restorative values than earlier daytime naps1,5.

- Naps in this zone generally contain less vital sleep stages and more light sleep; hence, it is easier to wake from them compared to earlier daytime naps.

- Age is also another noteworthy factor. In one study, adolescents may naturally have longer FZS duration than adults under no sleep deprivation7. This interpretation is made based on the results that adolescents struggled to fall asleep 2h before dim-light melatonin onset. Adults, however, did not have the same problem. Thus, age can be something to note when one schedules different polyphasic patterns.

How the forbidden zone is applicable in different polyphasic schedules

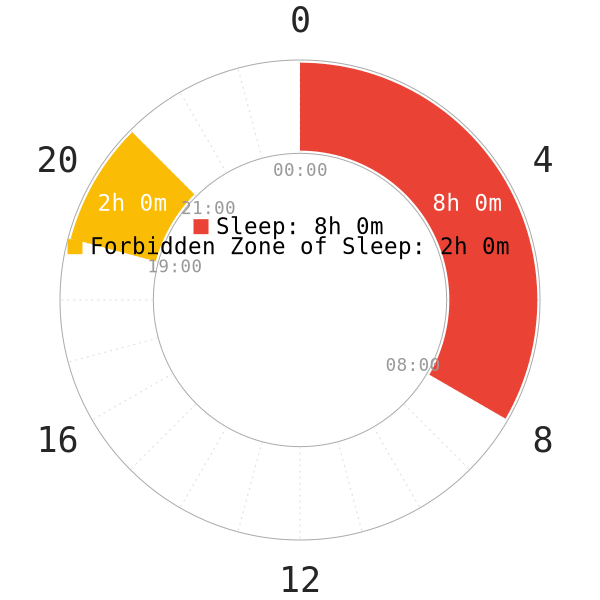

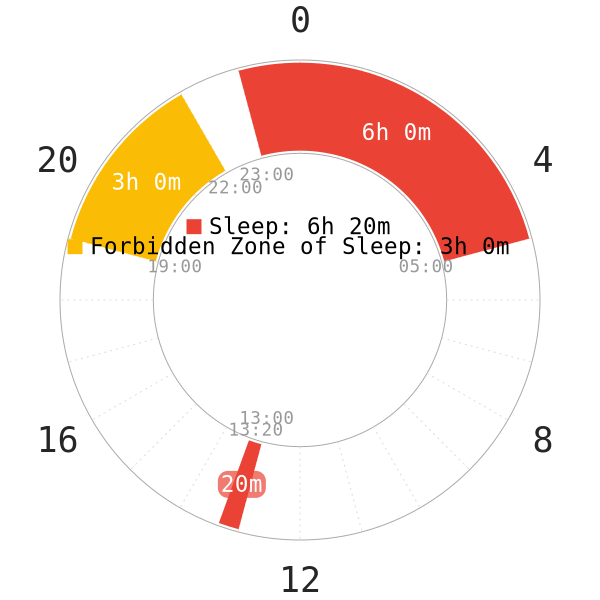

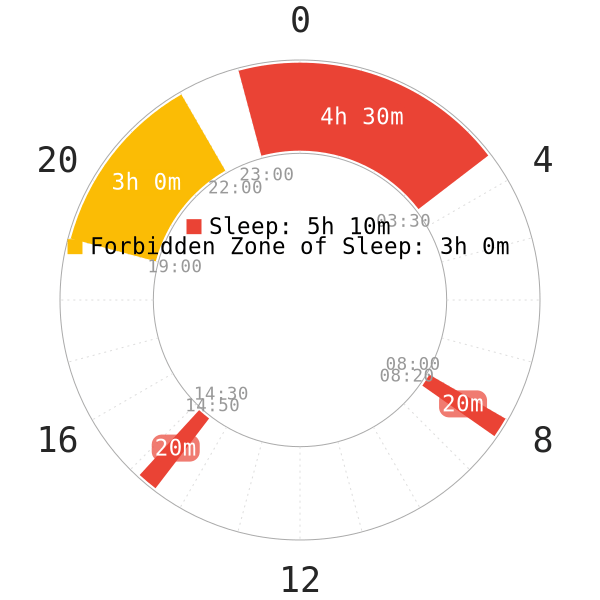

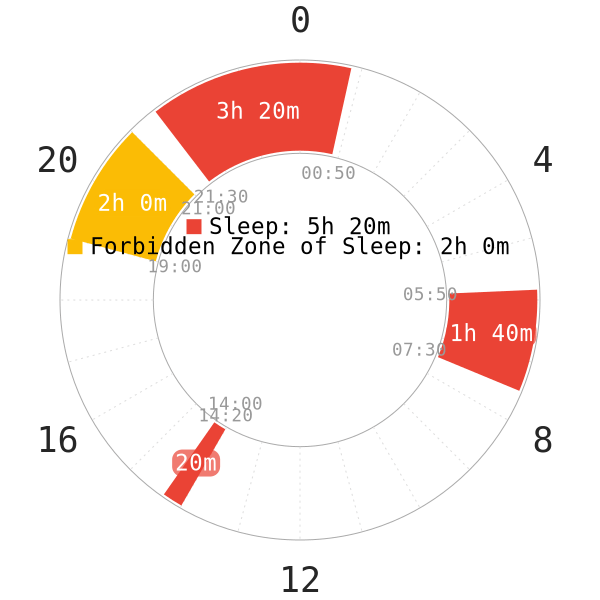

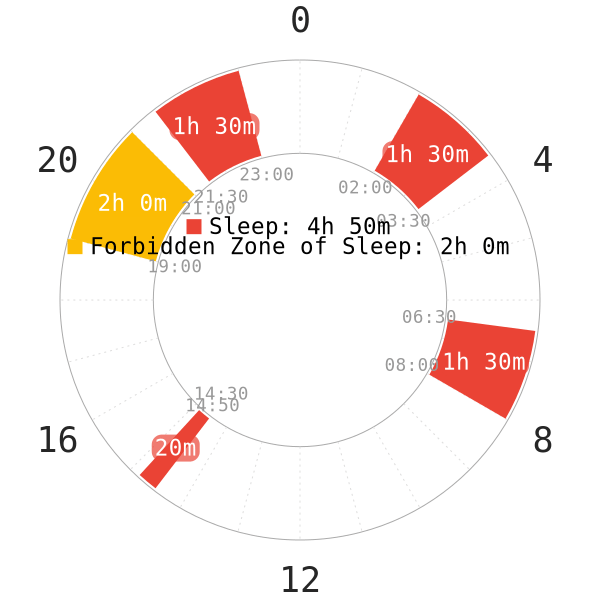

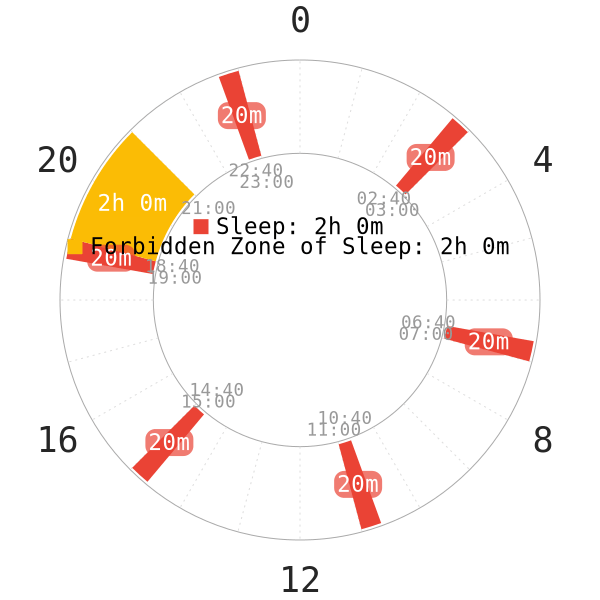

This section presents a theoretical visualization of FZS in different schedule groups, under normal scheduling conditions. The focus is on nocturnal sleep with added naps. Note that these illustrations of FZS can vary slightly from person to person (e.g, FZS duration).

Out of the four known nap-only schedules, SPAMAYL is the only one that appears to defy the normal FZS rules.

- The Uberman pattern can schedule around FZS hours by having 6 equidistant naps at different hours.

- Regarding SPAMAYL, it is unknown if chaotic napping can alter the timing of FZS. However, SPAMAYL have certain scheduling tweaks to avoid the normal FZS hours.

- While it is evident that some nap-only variants do not obey the traditional FZS hours, this is negligible. They require intense sleep deprivation to raise the homeostatic pressure to very high levels to be able to nap in FZS and effectively override its effects.

Deterministic behavior of the forbidden zone

Those who do not sleep in the normal graveyard hours (midnight to 08:00) probably set different FZS hours for themselves. Thus, those who have a shifted circadian rhythm will set different FZS. A lot of polyphasic sleepers have adapted to different sleep times in the day, whether their main core sleep is at the same or different hours than that of their normal monophasic routine.

As a result, the regular FZS hours may no longer apply in these scenarios. It may eventually become subjected to changes in sleep times.

Lifestyle & work shifts

A study on shift workers showed that different phases of the circadian rhythm determines the formation of FZS. This process is marked by melatonin onset8.

- Morning shift workers’ preferred habitual sleep time dictates sleep duration and there is an FZS.

- For example, those who have to wake up earlier in the morning for the shift work still sleep at their normal hours at night, which results in a reduction of night sleep duration. This sleep reduction is a result of their inability to sleep at earlier hours, not because of social commitments to stay awake in the evening hours.

- Another study supported the idea that FZS hours depend on habitual sleep times in each individual9. For example, those who sleep at 04:00 consistently may see their FZS start a couple hours leading up to 04:00, rather than the regular 19:00-21:00 range.

Additionally, it is important to consider sparing at least some waking hours apart from each sleep. This especially matters in polyphasic schedules with a shifted circadian phase. A well-defined, consistent bedtime on a daily basis will help shape FZS hours over time, regardless if the bedtime coincides with the timing of the nocturnal monophasic sleep. Thus, when there is a consistent phase shift in bedtime, FZS hours are affected and shifted accordingly.

Is it possible to erase the forbidden zone on a polyphasic schedule?

The short answer is likely no.

- It is likely that when the adaptation process is complete, sleepers will become familiar with the new sleeping hours. Their FZS may or may not be different from that on their monophasic schedule.

- It is worth noting that no research up to date has shown that FZS can vary on a daily basis; it rather appears to be set in stone.

- Completely random sleep patterns can weaken circadian cues, and eventually lead to a circadian desynchronization. Check Random sleep for more information.

- There may no longer be clear distinctions of day and night, similar to jet lag effects.

- Thus, having a stable circadian rhythm with a clear sleep-wake boundary is more suitable with consistency of sleep times. It is also likely safer and healthier to practice sleep hygiene to keep FZS consistent on a daily basis.

Conclusion

FZS is a very intriguing yet complicated concept. There are still a lot of unknowns in this area, as well as its interaction with certain hormones in the body. However, it seems the most important factors that manipulate FZS are personal bedtime and lifestyles.

Generally, it would be best to follow a stable sleep pattern with certain consistency to maintain a well-defined FZS and balanced hormones. However, the human body can adapt to different living conditions; and mainstream knowledge of nocturnal monophasic sleeping cannot exclusively be used to explain polyphasic sleeping mechanics1.

Main author: GeneralNguyen

Page last updated: 2 April 2021

Reference

- Stampi, Claudio. Why We Nap : Evolution, Chronobiology, and Functions of Polyphasic and Ultrashort Sleep. Birkhauser, 2014.

- José, et al. “The.” Sleep Science, vol. 4, no. 3, 2011, pp. 105–109, www.sleepscience.org.br/details/74/en-US/the–forbidden-zone-for-sleep–might-be-caused-by-the-evening-thyrotropin-surge-and-its-biological-purpose-is-to-enhance-survival–a-hypothesis. Accessed 20 Feb. 2020.

- Pereira, José Carlos, and Mônica Levy Andersen. “The Role of Thyroid Hormone in Sleep Deprivation.” Medical Hypotheses. 2014;82(3):350–355. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2014.01.003.[PubMed]

- Lastella, Michele, et al. “Sleep/Wake Behaviours of Elite Athletes from Individual and Team Sports.” European Journal of Sport Science. 2014;15(2):94–100. doi:10.1080/17461391.2014.932016.[PubMed]

- Naitoh, P., et al. “Sleep Inertia: Best Time Not to Wake Up?” Chronobiology International. 1993;10(2):109–118. doi:10.1080/07420529309059699.[PubMed]

- “Melatonin and Sleep – National Sleep Foundation.” Sleepfoundation.Org, 2019, www.sleepfoundation.org/articles/melatonin-and-sleep. Accessed Feb 20. 2020.

- Crowley, S J, and C I Eastman. “0248 Sleep and the Forbidden Zone: Trouble for Teens.” Sleep, vol. 41, no. suppl_1, Apr. 2018, pp. A96–A96, 10.1093/sleep/zsy061.247. Accessed 19 Dec. 2019.

- Folkard, S., and J. Barton. “Does the ‘forbidden Zone’ for Sleep Onset Influence Morning Shift Sleep Duration?” Ergonomics. 1993;36(1-3):85–91. doi:10.1080/00140139308967858. [PubMed]

- Lavie, P. “Ultrashort Sleep-Waking Schedule. III. ‘Gates’ and ‘Forbidden Zones’ for Sleep.” Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1986;63(5):414–425,. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(86)90123-9. [PubMed]