This page is an expansion from the Advanced Scheduling Section on the concept of flexing sleep. The strategies of flexing sleep in this page are based on past experiences of successfully adapted polyphasic sleepers. As such, these are mostly experimental ideas with the hope of making polyphasic schedules flexible and adaptive to daily lifestyle.

Being able to move polyphasic sleep blocks around is very appealing; in addition, if done right, it will help polyphasic sleepers maintain their sleep schedules. This is for sleepers who have successfully adapted to their respective schedules and want to pursue the napping lifestyle in the long term.

Content

- Introduction

- Mechanics of Flexing Sleep

- Lifestyle Consideration

Introduction

Flexible sleep timing (often shortened to just “flexing”) is the act of moving sleep times from day to day. This does not change sleep durations of the sleep blocks. This definition mostly applies to reducing polyphasic schedules; schedules that reduce total sleep time compared to personal monophasic baseline rather than non-reducing polyphasic schedules.

- Non-reducing schedules are inherently more flexible. They can have more varying sleep durations and random characteristics.

- Without any sleep reduction, there is a high amount of light sleep and total sleep as a whole. Thus, it is easier to move sleep blocks around. Sleepers can shorten or lengthen a sleep block without heavily affecting the inherent sleep architecture thanks to the light sleep buffer.

- This is especially true in the case of monophasic sleep (also non-reducing). Humans can sleep at different hours of the day in one go until they wake up. This allows the body to rake in an ideally sufficient amount of vital sleep stages, at the expense of a much longer sleep duration.

Therefore, the concept of flexing in polyphasic sleep only demonstrates its use in reducing sleep schedules.

- Vital sleep stages remain intact (after the adaptation phase).

- A certain amount of light sleep (mostly NREM2) will automatically reduce.

- With all these factors, flexing a reducing schedule requires proper timing, skills, sense of time and maintenance of all sleep blocks.

Additionally, flexing sleep is a powerful tool that can help sleepers maintain polyphasic schedules when daily timetables collide with the usual sleep times. This article will hopefully help polyphasic sleepers maintain their adapted polyphasic schedules. Hopefully, they will not have to revert to monophasic sleep if their daily timetable sometimes clashes with their usual sleep times.

Currently, flexing mechanics are not fully comprehended especially on different sleep patterns. For beginners, flexing sleep can be a rather challenging topic to understand.

Mechanics of Flexing Sleep

Adaptation Mechanics

One would wonder whether it is possible to adapt to a flexible polyphasic pattern, just as with strict schedules. And if it is possible, would the adapted state on a flexible schedule be the same as that on a strict schedule. The general rule of thumb is as follows:

- A full adaptation to a strict schedule is mandatory as a first step.

- Then, ideally stay adapted for several weeks (4-6 weeks) before attempting to flex any sleep blocks.

- Afterwards, it is possible to attempt to gradually move sleeping times of one or more sleep blocks.

- After being comfortable with a small flex range, sleepers can then increase the flex range gradually to adapt to the new flex range. The book Ubersleep by Puredoxyk also hinted that polyphasic schedules tend to become more flexible after the adaptation phase.

Thus, adapting to flexible, reducing schedules for the most part requires two separate adaptation steps:

- Strict base of a schedule

- Flexing sleep blocks

This second step, a flexing adaptation, is usually tamer than the first step. It also usually feels comparable to Stage 4 of a general adaptation. The flexing adaptation may slightly hinder personal well-being and productivity. This is a result of some manageable amount of sleep deprivation or mild tiredness as the body gets used to new sleeping hours. Successfully adapted flexing sleepers so far don’t report the full-blown sleep deprivation in Stage 3 that is almost always a part of adapting to a strict schedule.

Difficulty Level

Through this incremental flexing method, sleepers have been able to become fully accustomed to flexible sleep times from day to day as repartitioning stabilizes. However, the full adaptation to flexing varies; it may take longer to complete than the first adaptation step. These factors should be in consideration:

- The flex range of the core(s)

- How difficult the base schedule is.

- How many sleep blocks on the schedule would become flexible.

When flexing first begins, polyphasic sleepers can experience certain tiredness dips around the originally scheduled sleep time as a response to changes in sleep times. Bigger flex ranges will take longer to fully adapt to than smaller flex ranges. A full adaptation to flexing can take 4-8 weeks like a regular adaptation, with few oversleeps.

NOTE: It is important to keep flexed sleep blocks at least 90 minutes apart from each other to avoid forming interrupted sleep. This does not matter whether the gap is between the nap and the core or between naps. However, during emergency situations, it may become necessary to compromise this rule.

Why Cold Turkey Method Does Not Work

Cold turkey adaptations to flexible schedules in the community over the years largely lead to failures.

- Theoretically, this is because the body fails to recognize sleep times.

- The repartitioning of vital sleep stages is incomplete. This means attempters would hover between Stage 3 and 4.

However, very experienced polyphasic sleepers who have already adapted to a polyphasic schedule and then flexed the sleep times successfully in the past may be able to flex times slightly during new adaptations. If they are unable to do so, they will likely be able to start flexing nearly immediately after the new adaptation is complete. Meanwhile, beginners would often require more time to adapt. Thus, they are highly discouraged from attempting to flex sleep during adaptations to strict schedules.

Total Sleep Time

Depending on the total amount of sleep, flexing may require permanently adding 30 or 90 minutes to a core. This serves to buffer the reduced sleep efficiency of flexed sleep. This is also particularly a problem for schedules with very low total sleep times (e.g, Everyman 3, Dual Core 3, Uberman).

- Currently, it is viable for a base schedule to become flexible with a minimum of 5.5 hours of total sleep. This assumes that personal monophasic baseline is around 8 hours.

- People with a higher monophasic baseline (at least ~9 hours) may have a more difficult time flexing a regular 5.5-6 hour polyphasic schedule. This is because of a greater reduction in light sleep amount. Thus, flexing a sleep block should be done either sparingly or with a cautiously narrow flex range.

- As a known exception, several adapted Everyman 3 sleepers (4.5-5 hours total sleep) have been able to flex their 2nd and/or 3rd naps with a stable core sleep and fixed first nap.

Below are some tricks that facilitate flexing sleep in regards to total sleep time.

Core Extension

- Increase core length by 30 minutes: Everyman 2 core (5 hours) or Everyman 3 core (3.5 hours) are solid candidates. The sleep cycle length varies for everyone, and a 3.5 hour core has been proven to work. This makes it a viable option to try out. The 5 hour core is theoretically in line with the statistically-likely REM period.

- With proper sleep hygiene and normal sleep requirements, SWS usually occupies the first 3 cycles of a core in the night. REM sleep usually takes over the remaining sleep cycles.

- This small addition of sleep duration to a core length may make room for more REM sleep and protect REM requirements on the whole schedule more easily.

- Permanently increase core length by 90 minutes (a full cycle). This gives more light sleep buffer and alleviates homeostatic pressure on the other sleep blocks. In the process, it also facilitates flexing sleep.

The First Nap

- If there is more than one nap on the schedule, avoid flexing the first nap.

- This rule applies to Everyman schedules or schedules with a nap between 6-9 AM. This nap is primarily filled with REM sleep and usually contains little light sleep thanks to the circadian timing of REM sleep. Thus, it is necessary to preserve its quality by avoiding flexing it as much as possible.

- However, experienced polyphasic sleepers can flex this nap to some degree.

Core Flex

- Avoid flexing the core, or only to a small degree depending on the schedule. A core sleep is a “core” for a reason; it contains a lot more vital sleep stages than a power nap along with some amount of light sleep buffer.

- Drastically moving the core sleep around alters circadian influences on cycle architecture. This leads to changes in homeostatic pressure for the following sleep blocks.

- Changes in the overall sleep architecture can lead to destabilization. For example, an Everyman 2 core from 23:00 to 03:30 should not start at 01:00 (flex range of 2 hours) or later.

- If a big flex range has to occur (on very rare occasions) and the sleeper has been solidly adapted to the schedule for a long time, then it is possible to overcome this large flex range and gradually recover the following days.

- Currently, schedules with more than one core sleep and a total sleep of at least 5.5-6 hours theoretically tolerate core flexes better than Everyman schedules where there is only one core sleep. For instance, a second core can be useful in compensating for inconsistencies in the first one.

- Schedules with a core sleep of ~6h or longer may also make flexing easier at least to a small degree. Similar to nap flex, core flex should begin with small flex ranges (~15-30m in either direction) and then increase the flex range incrementally to gradually adjust to the new sleep times.

Late Naps

- Avoid placing naps close to the core sleep during flexing.

- Short naps evoke more grogginess if they are around SWS peak, graveyard hours or evening hours. They may contain SWS and result in heavy sleep inertia upon awakening. As a result, placing flexed naps from 19:00 to 03:00 is not recommended for schedules with a core sleep at night.

- Having late naps may also increase sleep onset latency for the core sleep at night. This would result in difficulty falling asleep and potentially ruin the core.

Conclusively, it is important to consider the total amount of sleep on the base schedule first. Then, think about how and which way to flex certain sleep blocks. Attempting to flex schedules with a low amount of sleep can destabilize the whole schedule and lead to oversleeps. Similarly, if the adaptation to a strict schedule is already too difficult, it will be unlikely to increase the overall flexibility of the schedule. Attempting these would then push the sleeper back to the previous sleep deprivation stages.

Differences between “-flex” and “-amayl” Schedules

See Flexible schedules for more information.

Lifestyle Consideration

Despite the inherent advantages posed by flexible schedules after the first adaptation step, it is necessary to consider appropriate lifestyles to afford either flexible or “-amayl” schedules.

There are two scenarios that flexible sleepers will have to face in their lifestyle:

- Sleep when tired enough

- sleep when required to

This section will detail different strategies to make use of sleep hours in various settings in hope of maintaining flexible polyphasic schedules.

Appetitive Napping

- This napping method is common in “-amayl” schedules.

- It can work occasionally in flexible schedules when flex range has become wide enough.

- In anticipation of unpredictable events some days, sleepers can lie down for a short nap (including naps less than 20 minutes). They do not need to be sufficiently tired or sleepy to do so.

- This napping method works for experienced and long-term adapted polyphasic sleepers. They can turn a shuteye into actual naps even without feeling very tired.

- Having small power naps at specific hours, especially during a small break gap goes well with appetitive naps.

- Even if the nap only contains NREM1, it can subjectively sustain wakefulness and performance to the next sleep block should the current timetable allow it.

The above scenario indicates the possibility of napping outside the adapted flex range once in a while. This also accounts for certain interruptions that prevent any sleep in the flex range. For example, it is useful when there is only one small work break for a nap.

- The adapted DC1 sleeper may not sleep as well as they would in the flex range. However, getting some sleep when they can is necessary to sustain wakefulness for hours that require concentration and performance.

- There is no time for a nap after the busy block; a nap then would interfere with the core sleep at night.

- If there is some time to cool down before the nap, regular tips on how to fall asleep during naps still apply. This includes, but not limited to wearing eye masks, finding a less noisy nap spot and focusing on breathing.

Prophylactic Napping

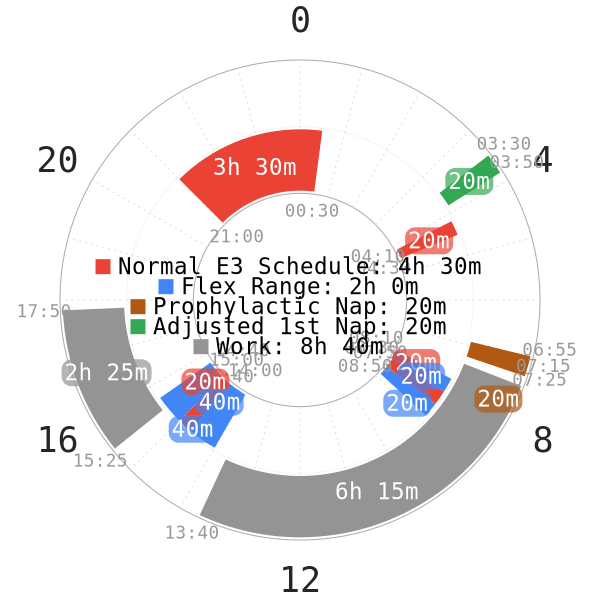

This is a term for how to effectively have a nap early, with minimal problems during a long waking gap. Instead of skipping the nap, adapted sleepers can arrange a nap/core earlier than usual to help stay awake. However, to make a prophylactic sleep effective, sleepers have to actually fall asleep in the nap. This may require taking prior sleep blocks slightly earlier. Shifting the schedule backward would pave the way for the prophylactic nap. See an example below.

- In this example, the second nap is out of the regular flex range. This is to accommodate for the busy work period.

- The adapted E3 sleeper can flex the first nap 35 minutes earlier than usual (Adjusted 1st nap) to make use of the second nap.

- Skipping the second nap entirely may be devastating to the schedule; additionally, it is not the only option if there is room to utilize flexing.

- However, even if the flexed nap is successful, there is still a chance that the nap will have less quality. This can increase the sleep inertia after the last nap of the day, or increase the amount of REM in the core.

- It may take some days of consistency to recover from the lost amount of vital sleep stage if sleep deprivation signs occur.

Food Intake & Exercising

Despite the flexibility of sleep timing, it is still possible to schedule meals and exercise times rather consistently.

- If a nap is slightly later than usual, it is a good move to eat right after waking up (e.g, lunch). This avoids conflict with the next sleep block in case it is too soon afterward.

- Eating too close to sleep time often decreases sleep quality. Thus, it is best to avoid this scenario and spare 2-3 hours from eating before each sleep, especially the core.

- Similarly, exercises can be after waking up from a flexed nap/core. This serves to prevent it from increasing sleep onset of the next sleep blocks (e.g, the core at night). Exercising before sleep keeps many people awake.

- However, there are exceptions on certain schedules.

- Adapted sleepers are aware that a certain nap on their schedule contains only NREM2 consistently (e.g, flexible E1 nap).

- When time is crunched, a meal can be ~1 hour before nap time.

As long as the sleepers can fall asleep in their naps, they will get NREM2 regardless. However, if the nap often contains some vital sleep stages (e.g, REM sleep), it is necessary to plan meals at least ~2-3 hours ahead to protect its quality.

Flex Range on Work Days

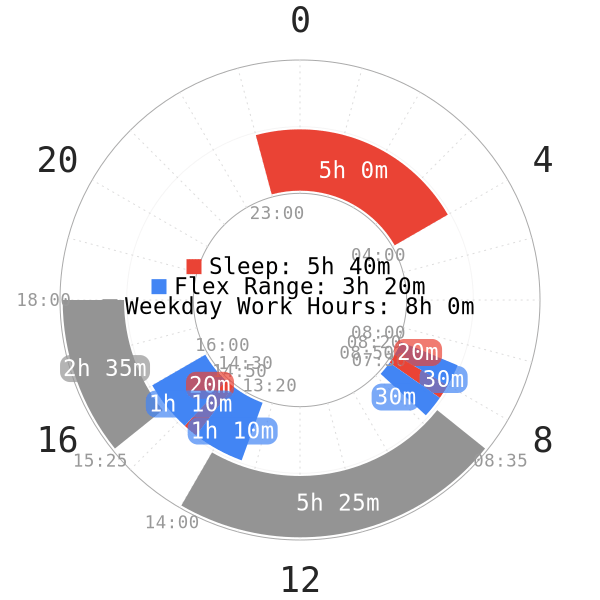

This applies to sleepers who have a fairly consistent schedule on work days throughout the week.

- The timing of each sleep block only varies within a small flex range during these days.

- Flex ranges can increase during weekends or holidays.

- For example, a daytime nap may only be flexible within 15-30m back and forth, around the original nap time. This eases prediction to schedule sleep times around certain hours with a familiar pattern of energy dips.

- For those with a consistent daily lifestyle, being adapted to, or aiming to adapt to a flexible schedule seems more appropriate than to an “-amayl” schedule. It is therefore important to see if the flex range is usually only small.

- The flexing adaptation is also easier with a slightly flexible schedule. The purpose of “-amayl” schedules is usually lost with a consistent timetable from day to day, which automatically limits the flex range of each sleep block and eliminates the freedom to sleep whenever tired enough.

Thus, it is necessary to look over individual lifestyles carefully before planning to adapt to either flexible or “-amayl” schedules.

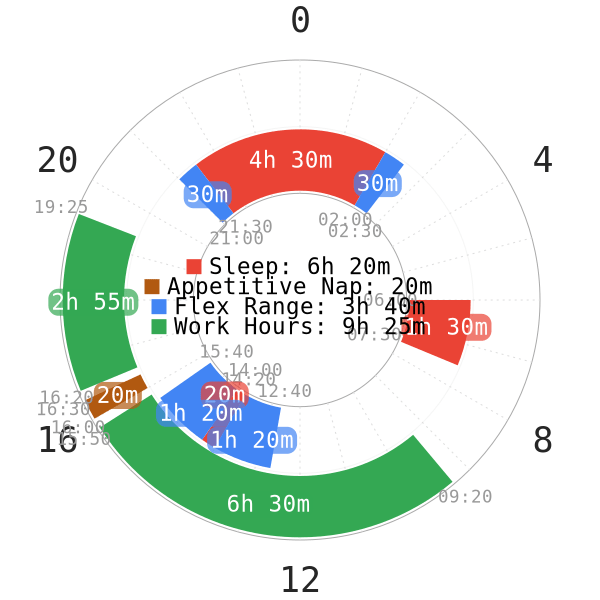

This is an example of an adapted E2 sleeper. He manages to have a flex range of 70 minutes in either direction for the second nap and 30 minutes in either direction for the first nap. Upon sketching his new daily work schedule after the flexing adaptation:

- He decides to reduce the flex range during weekdays to comfortably predict the second nap to fall between 14:15 and 15:00. This would keep the flow of the consistent work schedule.

- During weekends, he can increase the flex range of both naps to the previously adapted wider flex range.

Conclusion

In conclusion, flexing sleep can be a challenging yet necessary skill to acquire. This is if one decides to maintain the polyphasic lifestyle long term. It takes efforts, vigilance, a clear sense of personal wakefulness, tiredness dips and solid adaptation skills to make flexing a truly viable lifestyle. Flexing sleep requires two separate adaptation processes, with the second step being potentially longer yet milder than the first.

Sleepers should assess their daily timetables to decide on a flexible or an “-amayl” schedule. Currently, flexing the core sleeps seems more difficult than short naps. Thus, beginners should start with flexing the naps before the core sleep. It is also important to consider the total sleep time on the base schedules, how long the adapted state on the base schedule is, exercise, food intake and certain unpredictable events to schedule each sleep block properly.

Main author: GeneralNguyen

Page last updated: 2 April 2021