Introduction to Naps

We know that naps are an integral part of most polyphasic schedules. However, their duration matters.

- Naps should be mostly 20 minutes long. You can set alarms for about 22 minutes to account for time to fall asleep.

- Any naps longer than 25 minutes increase the chance of reaching SWS. During adaptation, SWS is prone to creeping in earlier as well; this makes 20 minutes the safest productive length.

Content

- Alternate Nap Durations

- Placement of Naps

- 30 vs 20-minute Naps

- Viability of 30-minute Naps on Other Polyphasic Schedules

- Minimum Nap Duration

Alternate Durations

- Some advanced schedules do use 30-minute naps to gain some SWS despite very little core time. Or, there is no sleep reduction on that schedule. Still, these are likely harder to adapt to. Beginners should avoid them.

- Naps can also be less than 20 minutes. If necessary, you could schedule two 15 minute naps instead of one 20 minute nap. This is less efficient because up to 5 minutes at the beginning of each nap is usually light sleep.

- During and after adaptation, however, naps often naturally decrease in length. Consequently, waking naturally after 15 to 18 minutes is totally normal. Additionally, some people wake naturally often around 8-12 minutes; however, that generally does not sustain enough wakefulness. They should instead return to sleep until their alarm to secure REM sleep requirements.

Placement

- Naps should be at least 3-4 hours, or 2 sleep cycle lengths apart. This ensures enough homeostatic pressure for quality naps, as well as ensuring the brain treats each nap as separate sleeps. Without separation, SOREM may not occur in later naps. Instead, you may fall quickly into SWS without the 25m sleep-initiation buffer. For more explanation, see Sleep Pressure.

- On most schedules, naps and sleeps are closer together from morning to midday hours. They can also expand further apart in the evening without losing wakefulness. This is usually a tactic for higher chance of REM occurring in the circadian morning.

- Occasionally, naps on extreme schedules will be at exact intervals to take advantage of subtle wakefulness rhythms, the BRAC cycles.

Adaptation to napping has occurred when most or all of your naps take advantage of SOREM.

- This is an emergency REM-preservation feature of the brain, mostly in narcoleptic patients. However, healthy individuals can still trigger this mechanic in reduced sleep polyphasic schedules.

- After just a couple or few minutes of light sleep necessary to transition from waking, you will fall into REM sleep for up to about 15 minutes.

- Until later in the adaptation process, naps will only consist of light sleep. They will be mildly refreshing, but REM pressure will steadily build; you will ultimately feel sleep deprived when the wakefulness from light sleep fades.

Other Notes

It is a bad idea to nap in the evening or at night.

- After about 14:00 or 15:00, the circadian REM pressure becomes low; on the other hand, the SWS pressure steadily increases toward the 21:00-midnight.

- In the evening and at night, naps commonly contain SWS after just minutes.

- The latest SWS-free naps that seem to work consistently are around 17:00 or 18:00 at the latest, based on anecdotes.

- Morning naps during “graveyard hours” (0:00-6:00) are more likely NREM2 up until the REM peak (06:00-09:00) when REM becomes most likely.

- Around noon, naps can contain both NREM2 and REM or only NREM2. This comes down to the sleep pressure of the schedule. For example, longer 90m siestas around noon will typically contain both SWS and REM.

30-minute Naps vs 20-minute Naps

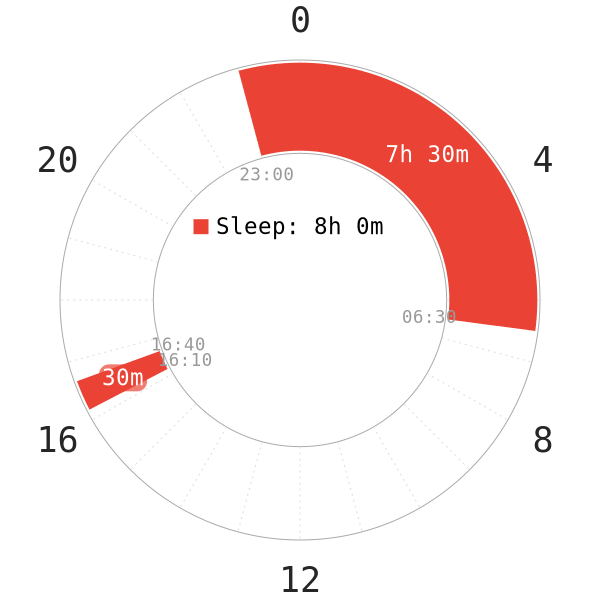

Although any polyphasic schedules can have 30m naps, scheduling them outside of non-reduced Biphasic patterns is not a good choice. As such, only the “-maxion” family of schedules capitalizes on 30m naps right from the beginning of the adaptation. Over the years, there have been more discoveries on the pros and cons of a 30m nap.

There are also very few polyphasic schedules with the design to have 30m naps from the start. All of these schedules are, however, related to the Dymaxion naps and have Dymaxion distribution of sleep.

Nap Duration

- The most noticeable difference is that these naps are longer than 20m naps by 10 minutes.

- Usually, sleeping longer than 25m (up to any duration below ~70-90m) will most likely lead sleepers to an SWS wake. This assumes that waketime programming hasn’t been achieved. When the adaptation first begins, sleep cycles remain as they are; in the naps, light sleep will initiate the transition from wake to sleep.

- This is the primary reason that makes them unpopular because of the requirement of extra willpower.

- In rare cases, some polyphasic sleepers may be more prone to 30m naps as they feel more “natural” than 20m naps. It is unknown why and probably comes down to exposure to both nap durations.

Recovery Power

- The longer duration also potentiate more recuperative effects than a 20m nap would.

- When sleep repartitioning is complete, a 30m nap may contain a higher percentage of REM sleep. This is for naps during early daytime hours.

- In addition, it also gives some amount of SWS if homeostatic pressure is high enough. The roles of SWS is fundamental for well-being.

Utility in Daily Lifestyle

- 30m shuteye sessions are short. Their duration makes it easy for them to fit into a normal daily lifestyle.

- However, a 20m nap may be superior in case the noon breaks do not allow for a 30m nap. All in all, the slightly longer duration is only a slight disadvantage for a 30m rest. Still, this largely depends on personal lifestyles.

- A 30m nap may be at a disadvantage with the dream recall opportunities, because of the SWS wakes. This suggests that the lucid dreaming potential may not be as strong on a 30m nap as on a regular 20m nap. However, adaptations to “-maxion” or any reducing polyphasic schedule can turn a 30m shuteye into a huge reservoir for dreaming.

- Excluding Pronaps, the first nap on Bimaxion can proliferate a lot of REM sleep once SWS repartitioning has stabilized in other sleep blocks.

Viability of 30m Naps on Other Polyphasic Schedules

Over the years, there have been more utilities that boost its niche. Below are certain conditions where these naps are viable.

Non-reducing Biphasic

The main idea is that most, if not all of SWS goes into the main nocturnal core sleep; the nap duration should only contain very little SWS. There have also been a few reports of natural wakes around the 30m mark.

- SWS pressure is often low when sleep reduction is absent. This assumes adequate sleep hygiene and a reasonably healthy lifestyle.

- For non-reducing biphasic sleep, the nocturnal sleep duration is basically the same as the monophasic core; thus, for the most part, SWS exerts little effects near the end of the nap. It is then easier to handle 30m naps.

- It may take some more minutes to actually fall asleep in the nap. This immediately reduces the chance for an SWS wake because of the longer sleep onset; this partially turns the nap into a ~20-25m nap instead.

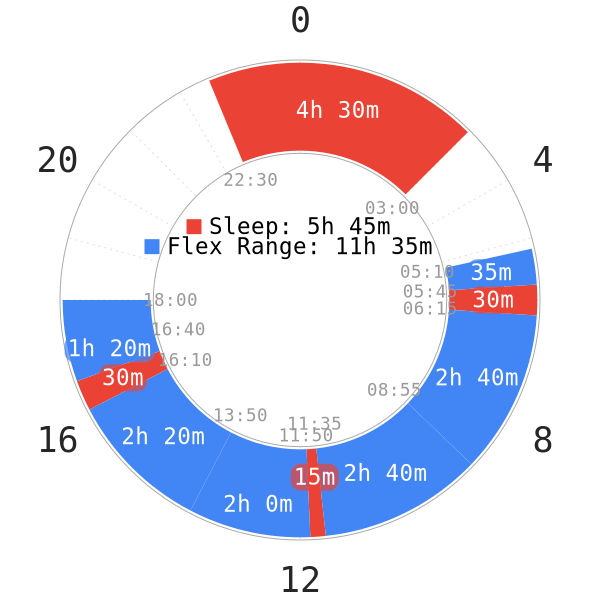

“-AMAYL” Polyphasic Schedules

- Since “-AMAYL” polyphasic schedules build on a fixed base schedule, they are expected to have mostly 20m naps at first. However, after adaptation, they do allow occasional changes in duration, including extension.

- The whole purpose is to avoid SWS wakes through this nap extension, without worrying about oversleeping. The first nap on SEVAMAYL is a Pronap in REM peak. The third nap is an extended nap out of REM peak.

- Because of the flexible nap timing, sleep onset for nap(s) is longer than on fixed nap times on a regular schedule.

- When sleepers do not have adequate time to wind down for a certain nap, they can utilize a 30m nap to buffer the time it takes to fall asleep.

- As an “-AMAYL” sleeper sleep for 30 minutes, they can then effectively skip their next nap for the rest of the day, or schedule fewer naps later on. This serves to accommodate their commitments by strategically abusing the longer nap duration. The slightly longer nap duration in the afternoon is to give some more rest after a more tiring day than usual. For this reason, this nap can fairly be a “compound 20m nap“.

Considering all elements, Bimaxion and other reducing schedules cause a very intense repartitioning of sleep stages. The Dymaxion naps’ behavior does not follow the logic of any casual 30m naps.

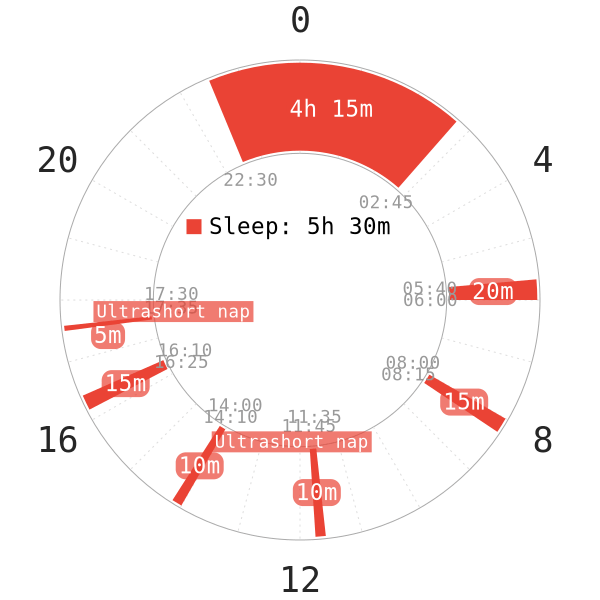

Minimum Nap Duration

There have been questions in the community whether naps can have varying durations, aside from the “requirement” that they all have to be mostly 20 minutes. Because this page has covered longer nap durations, this section will instead focus on ultrashort naps and their characteristics.

The goal is to find out the minimum duration of a nap so that polyphasic sleepers can still benefit from these naps.

History

Naps have had a long history of research. For the matter, the most relevant piece of information is the Continuity Theory of sleep. This theory states that a sleep session has to be continuous for at least 10 minutes to give some actual recovery for the body2. Based on this proposal, it suggests that a nap should be at least 10 minutes long to be effective.

However, is this true?

Viability of Ultrashort Naps in Polyphasic Sleeping

There has been instance of polyphasic sleeping with very short sleep sessions (10m or less). One of the winner sailors in the Transatlantic Race frequently used ~5-10m naps on his SPAMAYL variant1. However, the reason why these naps worked is because of the extreme nature of the nap-only schedule in practice.

Currently, there are anecdotes in the community regarding these naps.

Pros

- Suit extreme, restrictive polyphasic schedules. The reason is that sleep pressure is overall intense on these schedules; napping becomes easy without much preparation time to wind down.

- Fit sustained operation occupations. A quick shuteye of only ~5-10 minutes rather than the usually longer naps may still give some rest to continue with more strenuous tasks after awakening.

- Match flexible, “-AMAYL” and non-reducing schedules. These schedules typically do not care about either sleep repartitioning (non-reducing) or have various flexible mechanics.

- Experienced nappers can pick the correct timing to squeeze some actual sleep from ultrashort naps.

- Works well with emergency napping situations that do not allow strictly consistent sleep schedules.

- Under normal sleep conditions (e.g, biphasic sleep), it often guarantees to give little to no sleep inertia upon awakening.

Cons

Despite the seemingly promising con of ultrashort naps, the cons are also noticeable.

- Beginner nappers most likely cannot actually fall asleep.

- Often require preparation time before resting. Thus, this can be quite inconvenient since the rest session is so short.

- Limited recovery power compared to longer sleep. For example, 20-minute naps are still short and can sustain alertness much better.

- Detrimental to adaptation to strict schedules. During the intense Stage 3, just a quick shuteye of 5-10 minutes outside of sleep times counts as oversleeping and can turn into giant oversleeps. Furthermore, habitually dozing off during adaptation with these naps can force repartitioning of REM/SWS into them; this in return affects the overall sleep architecture of the schedule.

- More of a temporary and niched situations rather than a long-term or permanent lifestyle (except on biphasic schedules with short daytime naps). Longer nap durations simply outclass it.

Considering all factors, polyphasic sleepers should not schedule 5-10 minute naps in their schedules from the start. After adaptation, they will find these naps helpful in more stressful situations, however.

Conclusion

In sum, it is essential to understand the personal limits when scheduling different polyphasic schedules. Additionally, knowing the niches of certain “minimal” sleep durations can also help out with certain sticky situations. Either way, both of the minimum sleep values will hopefully be further studied and become more popular among polyphasic sleepers who want to pursue the lifestyle long-term.

Main author: Crimson & GeneralNguyen

Page last updated: 4 January 2021

Reference

- Stampi, Claudio. Why We Nap : Evolution, Chronobiology, and Functions of Polyphasic and Ultrashort Sleep. Birkhauser, 2014.

- Downey, Ralph, and Michael H. Bonnet. “Performance during frequent sleep disruption.” Sleep 10.4 (1987): 354-363.