Introduction

Diet considerations are often overlooked especially in first-time polyphasic sleepers. Unhealthy eating, has been associated with bad sleep; this is especially true with consuming little vegetables and high simple sugar contents1. Therefore, it is wise to actively manage personal eating habits to preserve the best quality sleep. Below is some information on common diets and eating habits. The list also shows how they might affect personal sleep quality and eventually polyphasic adaptations.

Common diet types

Low Carbohydrate/Ketogenic Diet

Some people in the Discord suggested that a ketogenic diet (low carbs, adequate protein, high fat) is helpful for polyphasic sleep. This is because:

- Consuming carbs increases cyclical tiredness and/or overall sleep need. However, so far only anecdotal evidence supports this claim.

- Hypothetically, the ketone metabolism supposedly minimizes cell oxidation relative to glucose. As a result, it may reduce tissue repairing time. There is a lot of research done on the topic, yet every individual research yields varying results.

- For example, some studies claim the ketogenic diet increases the amount of SWS and reduces REM.

- Some others say it decreases the amount of SWS for recovery.

Overall, further research on how ketogenic diet would directly affect polyphasic sleeping is mandatory.

OMAD diet

Although not one of the most common diet considerations, OMAD sees some use over years. Eating only one meal a day has anecdotally shown to cause no problems. This is if there is a long enough wake gap to the next sleep session. Make sure to reinforce the circadian morning; either with a daylight lamp or with sunlight if there is no breakfast.

Sugar

Sugar is a crucial component for diet considerations. Avoid consuming too much sugar or other carbohydrates.

- After sugar consumption, you get a boost in energy for up to 45 minutes. This may make it tricky to fall asleep.

- Abundant sugar mixed with plenty of fiber, protein, and/or fat should, however, reduce the intensity of the sugar high. Despite this effect, it still lasts up to a couple hours. When this wears off, you’ll reach an energy low for as long as a couple hours where you risk oversleeping.

- Your sleep quality will also suffer.

- Light sleep will replace SWS

- Sleep onset latency will increase,

- More sleep interruptions as you will be more prone to waking up in the middle of your sleep2.

High-carbohydrate diets have however been associated with significantly shorter sleep latency3. Yet, this may not matter as polyphasic sleep will decrease sleep onset naturally.

Protein

A low protein intake (<16% of energy from protein) correlates with poor sleep quality.

- It is also marginally associated with difficulty initiating sleep,

- A high protein intake (>19% of energy from protein) was associated with difficulty maintaining sleep4. But post-hoc test results showed that high-protein diets resulted in significantly fewer wake episodes than control diets3.

All of this means that the results are inconclusive. Furthermore, one cannot be certain how altering protein consumption will treat their sleep structure and requirements. Note that the latter study only had about 1% the participants compared to the former. Thus, fewer wakes has weaker evidence. It still remains clear that many people do get their sleep altered in some fashion from changing their protein consumption.

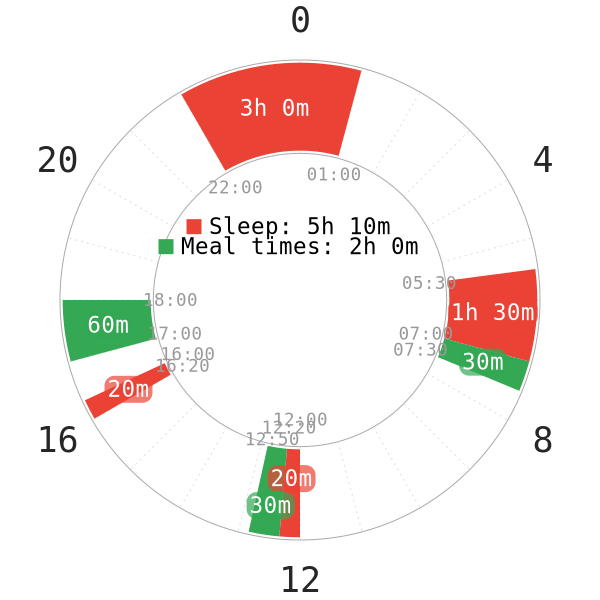

Eating time versus sleep time

It is generally better to eat just after waking up from sleep. This is to ensure your body isn’t having to digest food while sleeping, which reduces sleep quality5. Indeed, it can be very difficult to sleep with a full belly.

- When you eat, your stomach fills up with food. Then, pressure and receptors in your digestive system stretch with the stomach walls and notice an increased pressure. This effect lasts longer on high fat and/or high protein meals since they take longer to digest. Therefore, it stretches the stomach walls for longer periods of time.

- The parasympathetic nervous system gets engaged from the stretching, and prevents sleep. This is because energy directs towards digestion rather than sleeping.

- The aforementioned receptors are still active and constantly sending small signals to your brain. The process is unnoticeable, but results in a significant decrease in sleep quality; most importantly, it can sometimes cause even sleep interruptions.

- Also avoid excessive hunger, particularly if your body is not used to it. Some training should automatically happen during adaptation, however. It is important to keep a fast of at least 8 hours during the night; nighttime eating messes up the circadian rhythm and causes diseases like diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases. The safe bet is to avoid eating 2-3h before sleep; however, some light snacks up to 250kcal (like a banana) should be acceptable 1 hour before sleep.

- If you have limited time or a certain nap on your schedule always has only light sleep, you may eat with less wake time before the nap. However, keep in mind you may still wake up feeling more groggy with the reasons stated.

In conclusion, diet considerations are necessary and can facilitate nap quality. This in return can foster a smooth adaptation and stable eating habits.

Main author: Crimson

Page last updated: 2 April 2021

Reference

- St-Onge M-P, Mikic A, Pietrolungo CE. Effects of Diet on Sleep Quality. Advances in Nutrition. 2016;7(5):938-949. doi:10.3945/an.116.012336

- St-Onge M, Roberts A, Chen J, et al. Short sleep duration increases energy intakes but does not change energy expenditure in normal-weight individuals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(2):410-416. [PubMed]

- Lindseth G, Lindseth P, Thompson M. Nutritional Effects on Sleep. W. 2011;35(4):497-513. doi:10.1177/0193945911416379

- Tanaka E, Yatsuya H, Uemura M, et al. Associations of Protein, Fat, and Carbohydrate Intakes With Insomnia Symptoms Among Middle-aged Japanese Workers. J. 2013;23(2):132-138. doi:10.2188/jea.je20120101

- Crispim CA, Zimberg IZ, dos Reis BG, Diniz RM, Tufik S, de Mello MT. Relationship between Food Intake and Sleep Pattern in Healthy Individuals. J. December 2011. doi:10.5664/jcsm.1476