Introduction

Menstruation has always been a fascinating topic to explore, especially with regards to sleep. Accounting for individual differences, we have had exposure to a lot of different sleep reports. Regarding polyphasic sleeping, there is also a similar trend. There may be certain aspects that we can make generalizations on; however, given the complexity of the women body and sleep mechanics, the data still remain very limited.

In addition, we may hear thrown-around assumptions that women need more sleep than men overall, especially during their menstrual cycle. Nevertheless, breaking down every single mechanism of menstruation process will be more than painstaking. As a result, this post will only focus on the possible effects that menstruation can have on polyphasic sleepers.

Please note that there is very little research on the napping lifestyle and menstrual cycle. We hope that there will be intensive research on the polyphasic lifestyle and menstruation.

Menstruation Effects on Sleep

Menstruation is a natural cycle (ideally monthly) in the female reproductive system that enables pregnancy1. In addition, hormonal changes are present during this period and bleeding may last for a couple days. There may also be certain symptoms such as: acne, bloating and fatigue. For the focus of this post, we discuss the different phases of the menstrual cycle.

One cycle, the ovarian cycle, consists of the following phases2:

- Follicular phase

- Ovulation

- Luteal phase

Alternatively, the menstrual cycle can also occur in the uterus. There are also 3 distinct phases2:

- Menstruation phase

- Proliferative phase

- Secretory phase

During the menstrual cycle, the following effects can impact sleep:

- Sleep interruption, or WASO3

- Poorer sleep quality, which is more apparent with women who experience premenstrual symptoms3

- Elevated body temperature, but reduced temperature rhythm’s amplitude4

- Increased sleep onset latency and reduced sleep efficiency5. These effects may be more apparent in the late luteal phase compared to the mid-follicular phase6.

- Sleepers can spend more time in NREM2 and less so in SWS and REM in the luteal phase than in the follicular phase7.

- Disrupted circadian rhythm, which is more pronounced in third shift workers4

- Increased sleep spindles, but most likely because of progesterone and its metabolites3. However, the increase in NREM2 duration is usually insignificant.

Possible Menstrual Effects on Polyphasic Sleep

Even though there is ample, yet controversial evidence of how menstruation would affect sleep, not much is about polyphasic sleep. However, we did find some literature on napping during the menstrual cycle. Note that the results do not say all for every woman, especially polyphasic women. Below are some notable conclusions.

- It is possible to see some increase in SWS needs, because of the presence of SWS in daytime naps4. However, the luteal phase generally has a more prominent effect on SWS requirements rather than the follicular phase4.

- Another notable observation is that the boosted SWS needs have a positive correlation with changes in daily mean body temperature4.

- There is some decrease in REM duration in the luteal phase4.

- As said earlier, sleep spindle activity can drastically increase especially after learning or doing simple motor tasks8. However, they only reap the benefit of daytime napping in the luteal phase. Given that the 45-minute daytime naps contain purely NREM2, sleep spindles can assist with enhancing motor memory and memory consolidation.

Regardless, these conclusions fail to account for veteran polyphasic women, or seasoned nappers. In fact, sleep repartitioning changes during a polyphasic adaptation may imply that there is much more to overall sleep architecture, possibly even in the follicular phase. However, given that a lot of women over the world do practice biphasic sleep even naturally, such simple forms of polyphasic sleeping do not hinder a healthy menstrual cycle.

Community Anecdotes

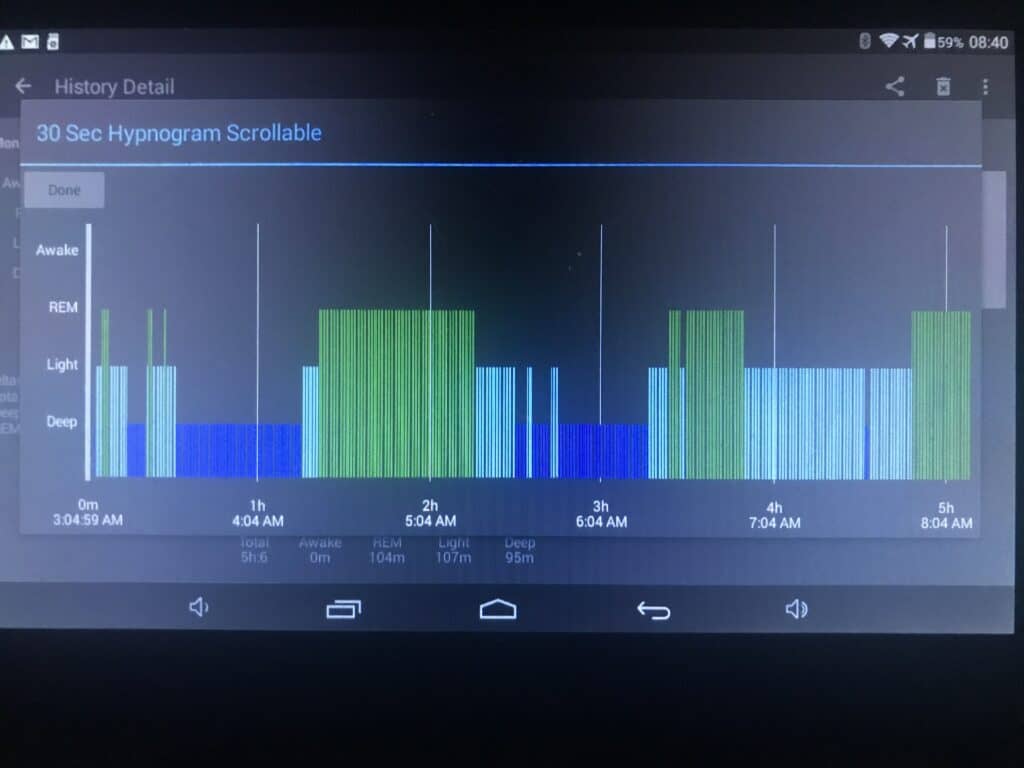

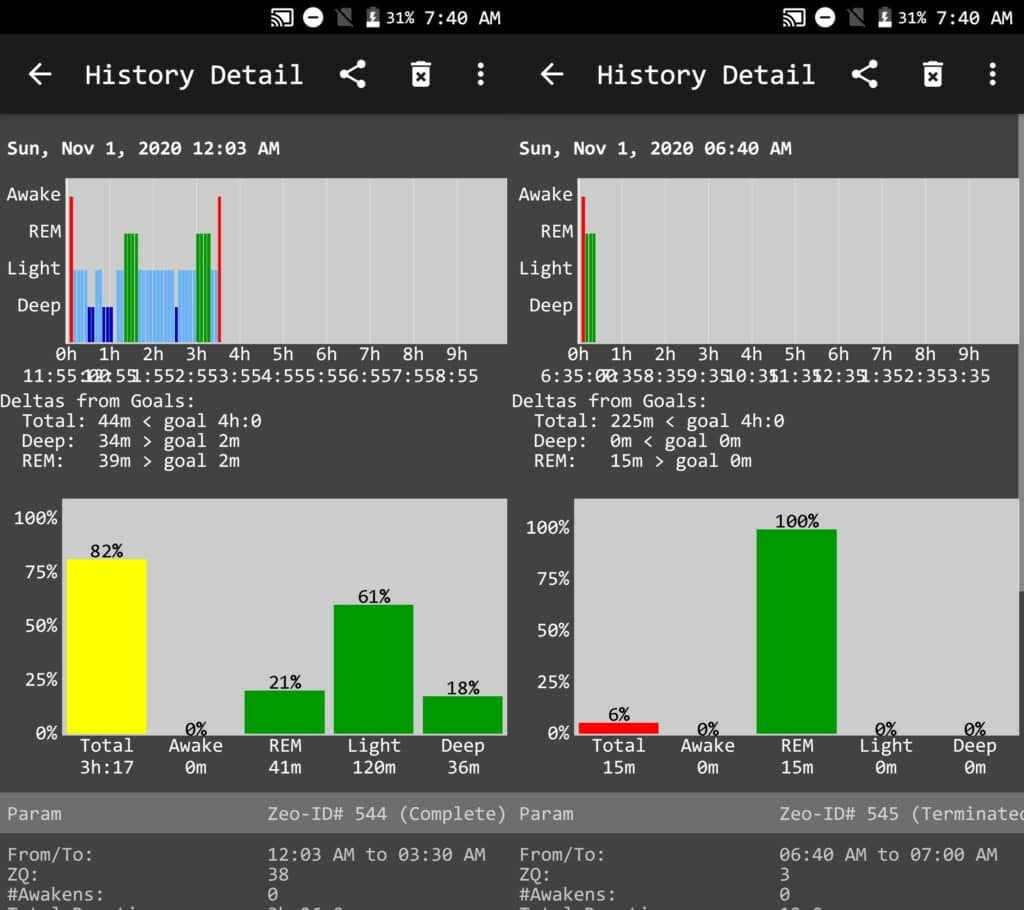

Menstruation and polyphasic sleeping remains a massively understudied topic in our community. However, over time, we did at least gather some Zeo readings of 2 short sleepers during their menstruation. Both of these women usually sleep no longer than 6h monophasically a day and qualify as short sleepers. Take a look at some readings below.

Legend:

- Green: REM sleep

- Dark blue: Slow-wave sleep

- Light blue: NREM2

- Red: Awake

Case 1

- This sleeper remarked incredible boosts to her vital sleep stages during one of her menstrual cycles.

- She did experience more dreaming, although she did also feel some menstrual pain.

- The reading was taken on day 3 of her period, while her periods usually last only 2 days. It is worth noting that this is a long oversleep on her SPAMAYL schedule. However, similar to certain sickness occasions, she was able to bounce back quickly, needing only short naps.

Case 2

- This sleeper experienced poorer sleep quality on her Biphasic-X schedule, a non-reducing prototype. This includes a very low percentage of SWS and REM, a high percentage of light sleep. She usually requires around 90m SWS and 60m REM daily for optimal performance.

- Poorer sleep quality also coincides with one of the aforementioned effects of menstruation on sleep. It seems to apply to even her adapted sleep. Note that she also experienced some kind of pain in her cycle, but not to the point of being unbearable.

- Although she did not record any extra EEG readings after this, she did report some increase in total sleep (rebound) but only on one day. Note that this was also a different menstrual cycle. On this day she slept a full 6h, but this was only because of a 4h TST on some days prior. This indicates that fluctuations in sleep duration and changes in sleep architecture match with common menstrual symptoms.

Overall, given the diverse outcomes and the small sample size of the community, it is reasonable to expect any of the documented effects. As a result, some of the effects are likely unpredictable for your own menstrual cycles. As one study said, individual differences in menstrual cycles produce a vast array in outcomes6.

Cautions & Other Notes

During a polyphasic adaptation, your period might be affected because of the hormonal imbalance. It might happen earlier, later or not at all. However, there are certain things you can keep in mind:

- Taking oral contraceptives can alter the circadian rhythm, core body temperature, sleep architecture and melatonin rhythm4. However, this should not be a big issue if you are adapting to a mild polyphasic schedule. Examples include any schedules with at least 6h sleep.

- The SWS needs can increase to some extent by each period. This means it is best to try to start adaptation right after the period. Alternatively, time it so that the period occurs during stage 1.

- Extending your core by a full cycle during this time might be necessary after adaptation (at least some days of the menstruation cycle). However, it is unclear and probably highly individual; schedules that have over 2 cycles in the SWS core may or may not require the extension.

- Over the years, we have seen a lot of polyphasic women adapt to their schedules.

- The schedules are also diverse, ranging anywhere from reducing Biphasic to Everyman 3 or even nap-only schedules in very short sleepers.

- After adaptation, they do not often complain about their period’s effects on their sleep.

- It is very possible that polyphasic schedules can still nullify sleep onset and WASO issues during the period. Or at least, in a way entrained polyphasic sleep helps maintain some levels of sleep stage efficiency.

Main author: Crimson & GeneralNguyen

Page last updated: 5 February 2021

Reference

- Sherwood L (2013). Human Physiology: From Cells to Systems (8th ed.). Belmont, California: Cengage. pp. 735–794. ISBN 978-1-111-57743-8.

- Silverthorn DU (2013). Human Physiology: An Integrated Approach (6th ed.). Glenview, IL: Pearson Education. pp. 850–890. ISBN 978-0-321-75007-5.

- Baker, F. C., & Lee, K. A. (2018). Menstrual Cycle Effects on Sleep. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 13(3), 283–294. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2018.04.002.

- Baker, F. C., & Driver, H. S. (2007). Circadian rhythms, sleep, and the menstrual cycle. Sleep Medicine, 8(6), 613–622. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2006.09.011.5

- Araujo, P., Hachul, H., Santos-Silva, R., Bittencourt, L. R. A., Tufik, S., & Andersen, M. L. (2011). Sleep pattern in women with menstrual pain. Sleep Medicine, 12(10), 1028–1030. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2011.06.011.6

- Van Reen, E., & Kiesner, J. (2016). Individual differences in self-reported difficulty sleeping across the menstrual cycle. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 19(4), 599–608. doi:10.1007/s00737-016-0621-9.

- Driver, H. S., Werth, E., Dijk, D.-J., & Borbély, A. A. (2008). The Menstrual Cycle Effects on Sleep. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 3(1), 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2007.10.003.

- Genzel, L., Kiefer, T., Renner, L., Wehrle, R., Kluge, M., Grözinger, M., … Dresler, M. (2012). Sex and modulatory menstrual cycle effects on sleep related memory consolidation. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(7), 987–998. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.11.006