Introduction

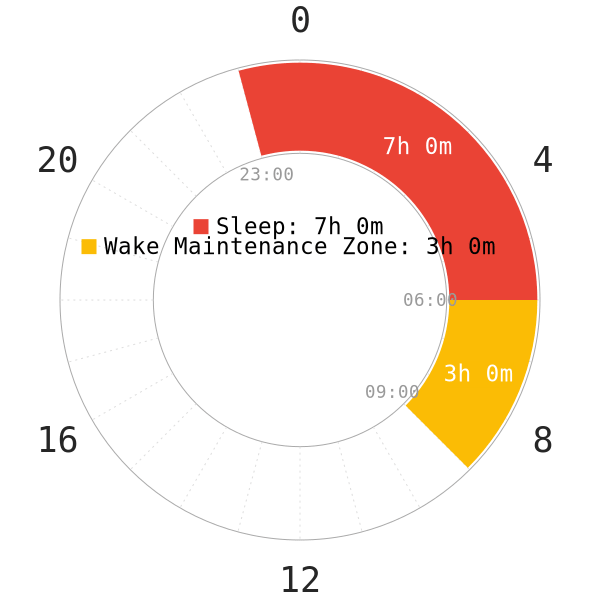

The wake maintenance zone (WMZ), by definition, is a period of wakefulness that lasts for 2-3 hours before nocturnal bedtime1. During this wake maintenance period, sleep propensity is usually low, which makes it very difficult to fall asleep. The WMZ definitely may vary between individuals, and how it may affect polyphasic adaptations remains interestingly unanswered.

Currently, there are anecdotal reports from the community do report the existence of the wake maintenance zone on polyphasic sleep. The most popular zone is still the hours before the nocturnal core sleep, even though the results vary. Thus, this post will attempt to explain the various mechanics and utilities of the WMZ for polyphasic sleepers.

Evening Wake Maintenance Zone

The definition focuses on the popularity of the evening wake maintenance zone, so the above post will detail its mechanics. Because of the definition, it is also sometimes referred to as “The Forbidden Zone of Sleep“. For the sake of this post, we will present the existence of other wake maintenance zones.

Other Wake Maintenance Zones

Under normal nocturnal monophasic sleep conditions, there can be more than one wake maintenance zone in the day. To differentiate from the forbidden zone of sleep, these are alternatively known as Second Wind2. As a result, these often give alertness boosts and prevent sleep, regardless of pre-existing tiredness levels.

Since your circadian rhythm cycles back into a phase you would usually be awake, this results in a massive burst of alertness.

- Morning WMZ: With normal nocturnal sleep, it is often common to stay alert for a couple hours after night sleep. This is because cortisol, the hormone whose levels rise near awakening, activates adrenaline3. Adrenaline in return facilitates glucose release and effectively prevents sleep4. Though it varies between individuals, a WMZ around 6-8 AM can be expected.

- Third wind: After second wind, you may hit third wind, etc. in 24-hour intervals. In a study with 40 hours of no sleep, a third wind was detected after 34.5h staying awake1. This already counts the wake maintenance zone in the participants before the study began. In addition, this third wind persisted for another 3 hours before completely subsiding.

Applications for Polyphasic Sleeping

Knowing that these zones exist is very important. Therefore, it is wise to avoid the following scheduling mistakes.

- While these are certainly extreme examples, over the years the community has observed multiple scheduling basic mistakes like these. All of these scheduling variants end up being unadaptable in the end. There are also very limited, if any, viable utilities with such short wake gaps between each sleep session.

- However, it is worth noting that the elderly often can nap in the evening WMZ without struggling to sleep at night5. On the contrary, younger adults have a longer wake maintenance duration in the daytime hours5. The young adults typically can only nap in the afternoon hours and can stay alert until night sleep.

Cautions

While potentially not applicable to every polyphasic sleeper, we still present certain cautions for your polyphasic adaptation.

- Those who are naturally familiar with a specific sleep time (e.g, late night), and attempt to switch to a sleep schedule with an early sleep time are bound to have insomnia.

- This is because their wake hours prior to sleep times constitute a wake maintenance zone. For example, a late sleeper who often sleeps at 2 AM likely will struggle if they attempt to switch to a Dual Core schedule whose first core starts at ~10 PM.

- It was observed that changing sleep habits by trying to shift personal circadian rhythm can result in both sleep onset insomnia and wake after sleep onset6. These individuals often have trouble initiating sleep and maintaining sleep in their own WMZ.

- Trying to sleep in this zone often results in mostly light sleep in the scheduled sleep. Sleep quality is shallow and not restful.

Solution to Wake Maintenance Zone

It is possible to bypass or curb the wakefulness effects of a WMZ. Follow these steps if you attempt to switch your sleep times with new sleep habits.

- Sleep less the previous night for a bit. For example, 3-4 hours less than your usual sleep duration.

Shifting circadian rhythm backward

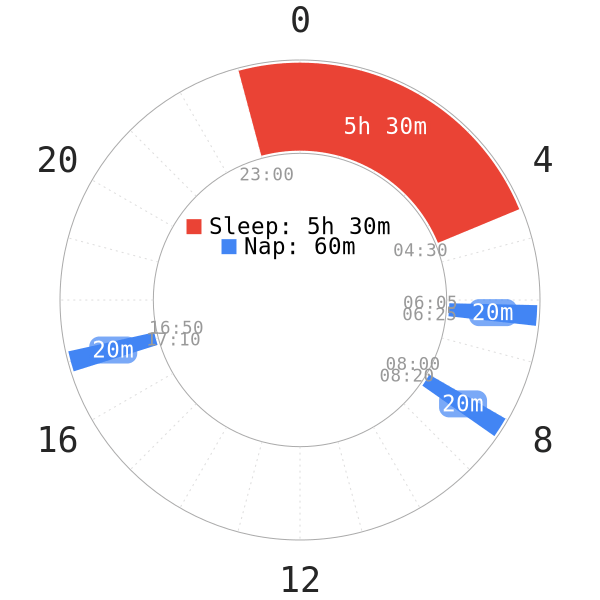

Skip the usual nap(s) the next day if you are shifting your circadian rhythm to an earlier hour. The shortened core sleep may facilitate falling asleep in the earlier core time. There is no guarantee, but this partial sleep deprivation tactic has worked for a few sleepers.

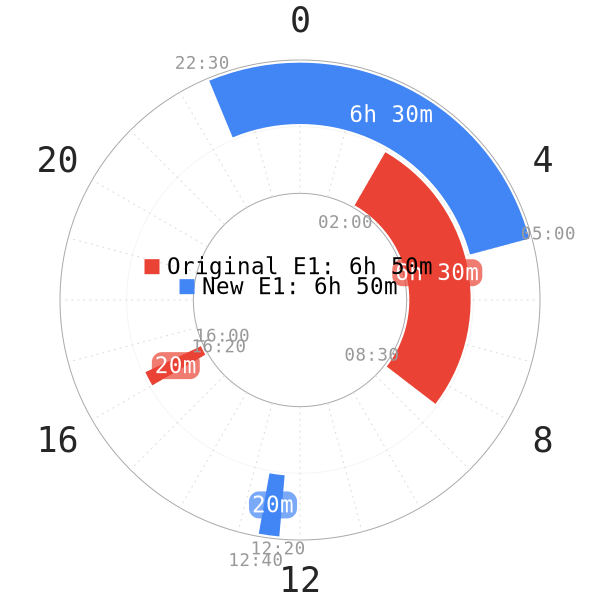

- In the Everyman 1 example, you can reduce your core length by 1.5h or 3h. If necessary, skip the nap at the original time, 4 PM.

- This hopefully will build up enough sleep pressure for you to fall asleep in the core at 10:30 PM instead.

Shifting circadian rhythm forward

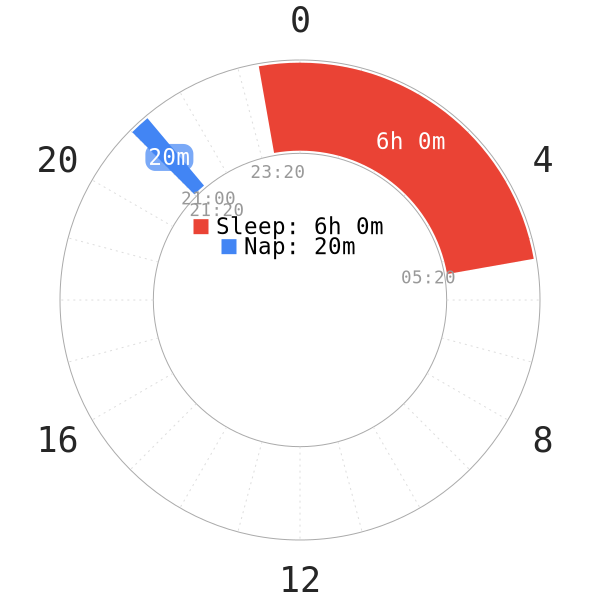

Alternatively, you may add a nap the next day if you are shifting your circadian rhythm to a later hour. Let’s look at an example.

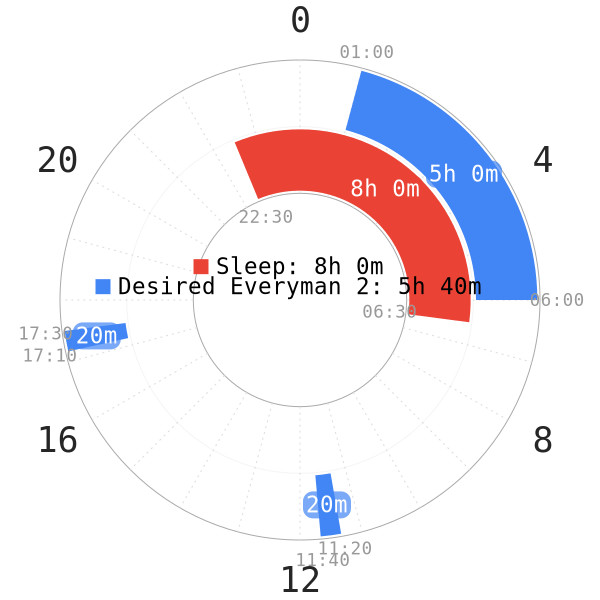

- Before starting E2, you can sleep a normal amount at night, and then start napping at 5:10 PM. This will be your second nap on Everyman 2 later on.

- Starting this nap may sustain your alertness and delay your bedtime to the desired 1 AM instead. This assumes you can fall asleep in the nap. This option is suitable for you if you do not have time to adjust your monophasic schedule and want to start E2 right away.

- As an alternative, you can sleep less on your monophasic schedule (1 night) to induce some more sleep pressure. This way you can make an immediate shift to 1 AM for the core. Keep this habit from then on by starting sleep at 1 AM instead. When this becomes stable, you can begin Everyman 2 adaptation.

NOTE: An “adaptation” to a different circadian timing is mandatory, regardless of how you are shifting your sleep time. Your WMZ will, as a result, shift to conform to new sleeping hours. Nevertheless, initially, you may find that you do not sleep as deeply as your previous bedtime.

Keep adhering to the new sleep time and over time you will get used to it.

Other notes

- The cold turkey circadian switch is usually more effective than the gradual method (e.g, 30m-1h switch incrementally everyday). Using some mild level of sleep deprivation can force a new change in sleep times; sleepers can even fall asleep in a WMZ because homeostatic pressure can override the wakefulness effects of a WMZ7.

- Ideally, though, you should align your current monophasic sleep times with the desired start time of your core sleep on a polyphasic schedule.

- For example, if you want to do Everyman 2 whose core starts at 11 PM, adjust your current sleep hours on your monophasic core to start at 11 PM as well.

- The same goes for a later core hour, the protocol does not change.

- Remain on the new sleep times comfortably before you start a polyphasic adaptation.

- Apply the dark period even on your monophasic schedule as well, to set the habits of using red glasses, etc. before bedtime.

Main author: Crimson & GeneralNguyen

Page last updated: 12 April 2021

Reference

- Zeeuw, J. de, Wisniewski, S., Papakonstantinou, A., Bes, F., Wahnschaffe, A., Zaleska, M., … Münch, M. (2018). The alerting effect of the wake maintenance zone during 40 hours of sleep deprivation. Scientific Reports, 8(1). doi:10.1038/s41598-018-29380-z.

- Shekleton J, Rajaratnam S, Gooley J, Van R, Czeisler C, Lockley S. Improved Neurobehavioral Performance during the Wake Maintenance Zone. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(4):353-362. [PubMed]

- Wilson JL. Clinical perspective on stress, cortisol and adrenal fatigue. A. 2014;1(2):93-96. doi:10.1016/j.aimed.2014.05.002.

- Brunshaw, Jacquelinee (July 31, 2012). “Paying the sandman: Bad night patterns, chronic sleep debt and risks to your health“. National Post.

- Yoon, I.-Y., Kripke, D. F., Youngstedt, S. D., & Elliott, J. A. (2003). Actigraphy suggests age-related differences in napping and nocturnal sleep. Journal of Sleep Research, 12(2), 87–93. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2869.2003.00345.x. [PubMed]

- Lack, L. C., & Wright, H. R. (2007). Treating chronobiological components of chronic insomnia. Sleep Medicine, 8(6), 637–644. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2006.10.003. [PubMed]

- Lastella, Michele, et al. “Sleep/Wake Behaviors of Elite Athletes from Individual and Team Sports.” European Journal of Sport Science. 2014;15(2):94–100. doi:10.1080/17461391.2014.932016.[PubMed]